Wildlife damage management is an established part of the wildlife profession. Animals often end up in the wrong place, at least from a human perspective. Mice in the pantry, skunks under the deck, bats in the attic. But on September 9, 1945, getting rid of unwanted nature took on a new meaning.

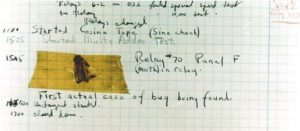

On that date, Dr. Grace Hopper was part of the team of mathematicians and electrical engineers at Harvard working on the Mark II computer. The machine was acting up, and the team couldn’t diagnose the problem. Eventually, they discovered the issue: a live moth was stuck in a relay, causing it to malfunction. Hopper removed the moth from the relay and taped the critter into the day’s log at 3:45 PM, with this note: “Relay #30. Panel F (moth) in relay. First actual case of bug being found.”

Bugs are part of nature, in positive and negative ways. Bugs make up half of all known species and outweigh the human population of the earth by about 300 times. But this bug was special. With it, a new era and a new terminology was coined. The term “bug” had been in use in engineering for some time, as an expression of problems in a device or process. But when Hopper discovered an actual bug being the cause of a problem and then immediately coined her action to remove the offender as “debugging,” a new era was born.

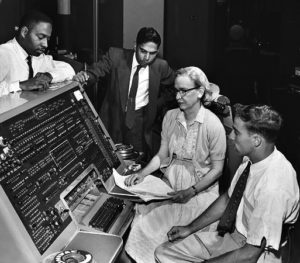

So, the bug is the focus of today’s entry, but the star is Grace Hopper. She became one of the world’s most influential computer scientists, working for four decades with the Navy, as both a reserve officer and an active duty member. She joined the Navy in 1943, as a member of the WAVES—Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services—and finally retired in 1986 as a Rear Admiral, the oldest living active duty navy officer at the time.

Hopper was born in 1906 (died 1992), in New York City, and earned a BA at Vassar, in math and physics—a rarity in that time. She taught math at Vassar while studying for her advanced degrees at Yale. Now Dr. Hopper, she moved on to Harvard to work on early computers. Her work as a naval reserve office also focused on computers, and her military and personal careers were never far apart.

She had a creative mind, believing that “we’ve always done it that way” was no excuse for shunning innovation and experimentation. As one observer wrote, she “appears to be all navy, but when you reach inside, you find a ‘Pirate’ dying to be released.” She rejected the idea that computers could only do arithmetic, or that programming computers had to be all Os and 1s. She developed the first “compiler” that converted English language instructions into machine language, ushering in the age of accessible programming in languages such as COBOL.

Grace Hopper is one of the most heralded leaders in the development of early computers. Known by her colleagues as “Amazing Grace,” she was the first person to be named “Man of the Year” in computer sciences, in 1969. President George Bush awarded her the National Medal of Technology, just before her death in January, 1992. In 2016, she was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama. During her life, she received 40 honorary doctorates, and a naval military vessel, the USS Hooper, is named after her.

But we will always remember her as the person who literally “debugged” a computer!

References:

Engel, Kerilynn. 2013. Admiral “Amazing Grace” Hopper, prioneering computer programmer. Amazing Women in History. Available at: http://www.amazingwomeninhistory.com/amazing-grace-hopper-computer-programmer/. Accessed September 8, 2017.

Markoff, John. 1992. Read Adm. Grace m. Hopper Dies; Innovator in Computers Was 85. New York Times, January 3, 1992. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/1992/01/03/us/rear-adm-grace-m-hopper-dies-innovator-in-computers-was-85.html?mcubz=0. Accessed September 8, 2017.

Yale University. 1994. Grace Murray Hopper. Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing. Available at: http://www.cs.yale.edu/homes/tap/Files/hopper-story.html. Accessed September 8, 2017.