One of America’s most ambitious projects—economic and environmental—began on March 27, 1975, when the first pipe was laid for what would become the Trans Alaska Pipeline. After years of debate about the value and possible impact of the pipeline, the outcome has been remarkably positive.

Oil was discovered in the far north of Alaska in March,1968. The location was Prudhoe Bay, adjacent to the northern shore of Alaska, 100 miles above the Arctic Circle. The find turned out to be the largest oil field ever discovered in the United States, estimated at the time to contain about 10 billion barrels of recoverable oil.

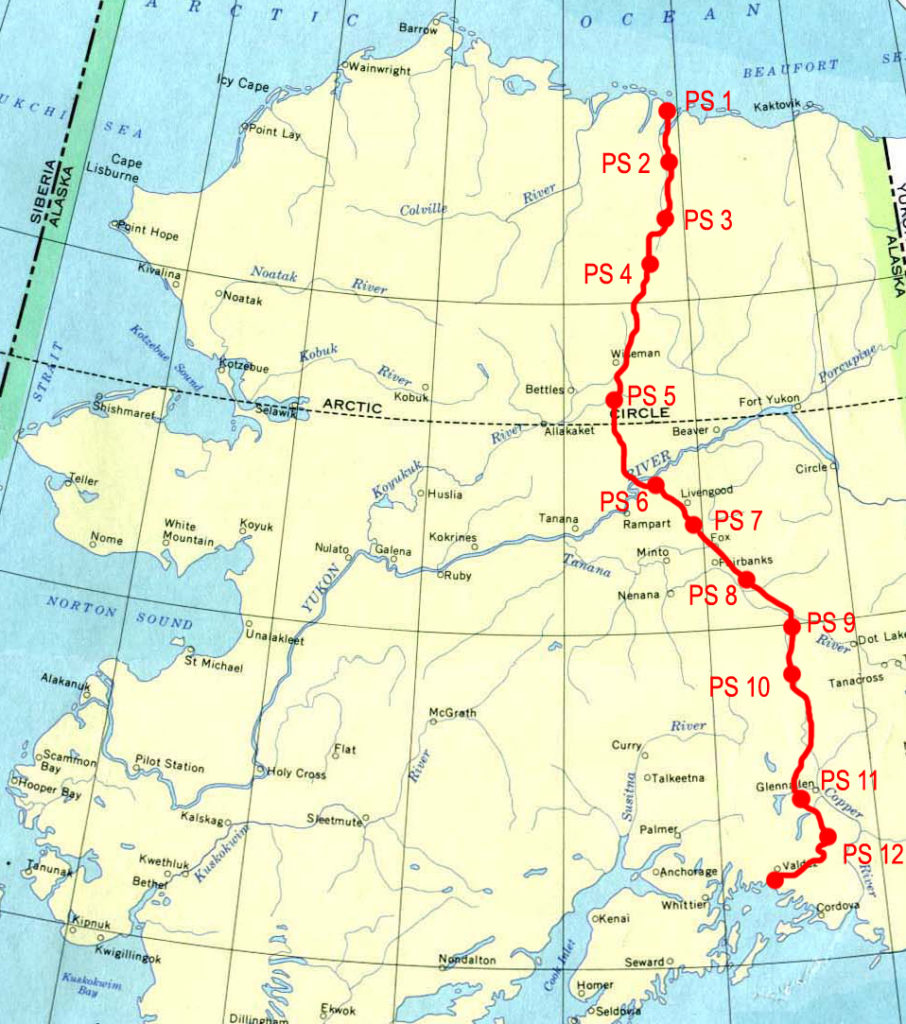

The problem, of course, was how to get the oil from the North Slope of Alaska to the rest of the country. The sea was frozen for much of the year, preventing oil tankers from carrying the oil to other locations. The solution was to build a pipeline to the nearest port that was ice-free all year long. That port was at Valdez, Alaska, on the state’s southern shore, 800 miles from the oil field.

Distance wasn’t the only problem. A pipeline from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez would need to cross three mountain ranges, span 34 major rivers and 700 smaller streams. It would pass through a major earthquake zone—and Alaska was known for its severe earthquakes. Temperature extremes were brutal, from frigid cold to blistering heat. The route also passed through “permafrost,” the permanently frozen ground that would melt if it was disturbed, breaking a buried pipeline.

There were also major issues of land ownership, involving Native Americans in Alaska and state versus federal land holdings. And at just about the same time, the National Environmental Policy Act was being passed, requiring impacts statements about a place that was poorly known and a project of a type and scale that had never been tried before.

Amidst all these issues, however, the oil producing countries of the Middle East slapped an embargo on oil exported to the United States. Oil supplies dropped, causing prices to rise and shortages to affect the lives of every American (read about the oil embargo here) . Faced with the possibility of no gas for cars, the federal government quickly responded, solving Native American land issues, environmental processes and other impediments and approving the “Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act” in 1973.

And, so, on March 27, 1975, the first section of pipe was welded into place. The pipeline was finished on May 31, 1977—with a “golden weld” reminiscent of the golden spike that completed the trans-continental railroad a century earlier (read about the golden spike here). It has proven to be an engineering masterpiece. Of the 800 miles, about half are buried, in the normal style of pipelines. The other half of the pipeline, however, could not be buried because of permafrost. Instead, the pipe is suspended on masts that hold it several feet above ground. The masts are called “vertical support members,” or VSMs. Invented for this purpose, they contain liquid that transfers heat from the masts and the adjacent ground, keeping the permafrost frozen and the pipe securely mounted.

The pipe itself sits loosely on the supports, so that it can move with changes in the local topography. The path is a zigzag, which allows the pipeline to move more extensively during earthquakes, without rupturing. Although Alaska has experienced many earthquakes during the 40-year life of the pipeline, no earthquake related leaks have occurred.

When the pipeline was planned, the impact on caribou was a major concern. Some predicted that caribou would not cross the pipeline, either by passing under it or going over it where passages were provided, causing disruption of breeding and decline of the populations. Happily, caribou have proven quite resilient. The population most likely to be affected, the Central Arctic Herd, had about 5,000 animals in the mid-1970s. It has grown steadily, reached more than 70,000 in the early 2000s and now numbering about 25,000 (all caribou populations in Alaska have undergone large fluctuations in abundance in this century.

In general, the environmental impacts of the Trans Alaska Pipeline have been minimal, especially when the massive nature of the project is considered. The pipeline has carried 17 billion barrels of oil over its life, an average of 1.8 million barrels per day. At one time, the pipeline produced 20% of America’s domestic oil supply. Sometimes, the system gets it right.

References:

Alyeska Pipeline. Pipeline Facts. Available at: https://www.alyeska-pipe.com/TAPS/PipelineFacts. Accessed March 25, 2019.

American Oil & Gas Historical Society. Trans-Alaska Pipeline History. Available at: https://aoghs.org/transportation/trans-alaska-pipeline/. Accessed March 25, 2019.

Circum Arctic Rangifer Monitoring and Assessment Network. Central Arctic Herd. Available at: https://carma.caff.is/herds/538-carma/herds/589-central-arctic. Accessed March 25, 2019.

Hobson, Margaret Kriz. 2017. How Spiro Agnew helped save the Trans-Alaska project. E&E News, August 8, 2017. Available at: https://www.eenews.net/stories/1060058484. Accessed March 25, 2019.