Canadian fisheries officials had warned the Spanish government that they would not tolerate overfishing on the Grand Banks, Canada’s most important fishing location. But Spanish trawlers ignored the warning and continued to fish. On the morning of March 9, 1995, Canada took action, capturing a Spanish trawler. And the “Turbot War” had begun!

The Grand Banks is one of the most prolific fishing grounds in the world. The relatively shallow waters (averaging about 200 feet deep) are rich with plankton, the floating plants and animals that serve as food for small fish and larger invertebrates. In turn, those organisms feed larger fish. Huge populations of cod and similar species (including Greenland halibut, or turbot) had attracted fishermen for centuries. Not just Canadians from Newfoundland and Americans from New England, but also seafaring fishermen from Spain and Portugal, exploited the Grand Banks

But in the years after World War 2, the fishing had become so intense that stocks of the major species were declining. In the 1970s, Canada (along with other nations around the world) began enforcing a greatly expanded territorial limit, out to 200 miles from shore. This put most of the Grand Banks into Canadian control. To protect the dwindling stocks, Canada instituted strict limits on the numbers and sizes of fish that could be caught. Cod was the most important species, and had been so depleted that in 1992 Canada eventually banned all fishing for cod for several years to let the stocks recover.

Spain bristled under the constraints on its fishing, arguing that part of the Grand Banks was still in international waters and, therefore, they could fish there without Canadian permission. Canada countered that under the Law of the Sea, it had the right to regulate fisheries that straddled national-international boundaries. Overall fishing regulations are set by the North Atlantic Fisheries Commission, which lowered quotas on most species and instituted other restrictions (such as size of mesh in the trawls and times of fishing).

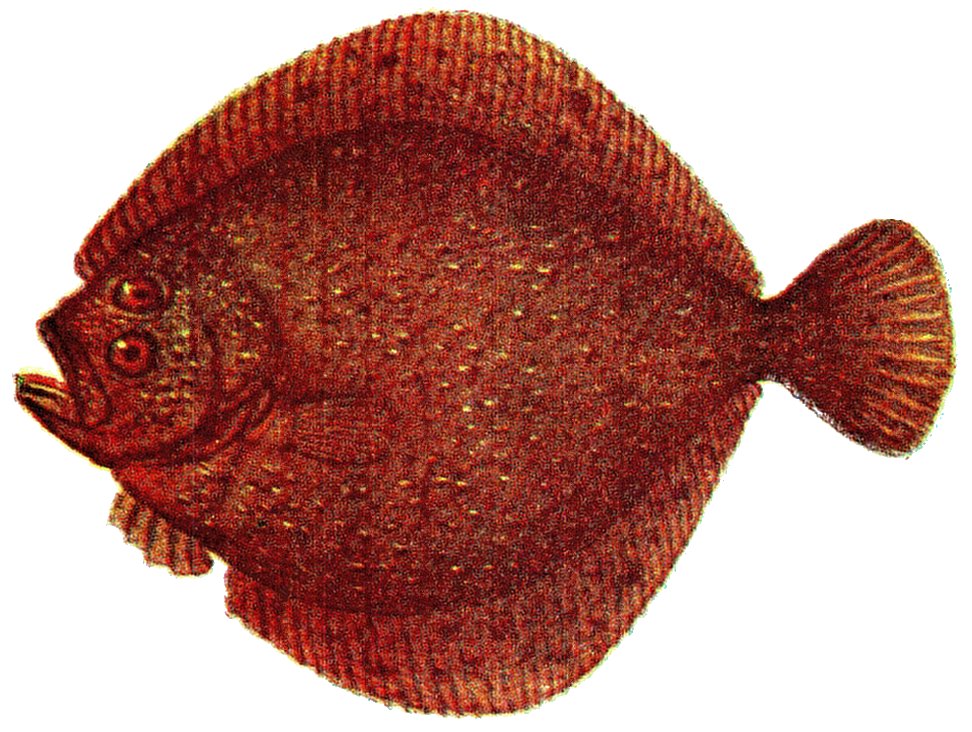

Things were gradually getting worse, and Canada finally decided it had to act. With cod populations virtually gone, fishing had turned to the turbot, a flatfish highly desired for its mild taste. The fisheries minister from Canada, Brian Tobin, lamented the case of overfishing, saying, “We are down to the last, lonely, unloved, unattractive little turbot, clinging by its fingernails to the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, saying ‘Someone, reach out and save me in this eleventh hour as I’m about to go down to extinction.’” Fearing that turbot populations were going to suffer the same fate as cod, Canada told Spain to stop fishing for turbot on the Grand Banks. Again, Spain objected and warned that they would send gunboats to protect their fishing fleet.

But this time, the generally non-confrontational Canadian government chose to act. On March 9, 1995, Canada sent patrol boats to board and seize the Spanish trawler, Estai. When the Royal Canadian Mounted Police tried to board the ship, the Estai threw off their ladders and gunned their engines to outrun the Canadians. After a four-hour chase, the Canadians were authorized to shoot at the ship and fired four shots across the Etsai’s bow. The Etsai surrendered and was towed to shore in St. John’s harbor, where thousands of jubilant residents cheered on their conquering heroes. Within the hold of the Etsai, Canadian officials found tons of turbot below the allowable size and more tons of American plaice, a fish that had a zero catch-quota. The nets of the ship also had illegally small mesh sizes.

Two weeks later, Canadian officials also cut off the nets of three more fishing boats, two from Spain and one from Portugal. The European Union Fisheries Commissioner called these acts of “organized piracy.” Thankfully, that was the end of hostilities. The countries returned to diplomacy to resolve the problem, and by mid-April, they had agreed on new restrictions and quotas.

Conditions have improved since then. Cod stocks are recovering and limited fishing has begun. Similarly stocks of turbot are slowly recovering as well. And, so far at least, no one has had to call out the Canadian Mounties again!

References:

Anderson, Lisa. 1995. Depleted Fish Stocks Spark Canada’s Turbot War with Spain. Chicago Tribune, March 19, 1995. Available at: https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1995-03-19-9503190138-story.html. Accessed March 5, 2019.

Barry, Donald, Bob Applebaum and Earl Wiseman. 2014. The Turbot War: A look back at how Canada stood up to foreign overfishing (book excerpt). National Opinion Centre, Jul 19, 2104. Available at: https://www.nationalnewswatch.com/2014/07/19/the-turbot-war-a-look-back-at-how-canada-stood-up-to-foreign-overfishing-book-excerpt/. Accessed March 5, 2019.

Encyclopedia Britannica. Grand Banks, Atlantic Ocean. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Grand-Banks. Accessed March 5, 2019.

EU Learning. Turbot War. Available at: https://carleton.ca/ces/eulearning/geography/turbot-war/. Accessed March 5, 2019.