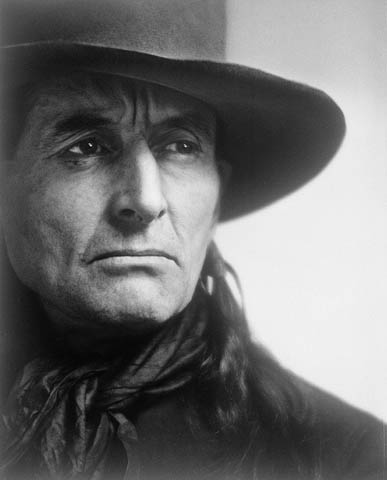

A lobbyist once told me that all things are like pancakes—they all have two sides. Today’s story is about a man who certainly had two sides, two very complex and very confusing sides. The man is Grey Owl, one of Canada’s earliest conservationists, and an imposter on a grand scale.

So, let me first tell you about Grey Owl, the conservationist. Grey Owl—his name meant he-who-flies-by-night in the Ojibwa language (a bit of foreshadowing…), was half Native American and half Scotsman, but he chose to live as an Ojibwa Indian in northern Canada. There he learned the ways of the wilderness, hunting and trapping to earn a living and survive, winter and summer, for decades. He met a Mohawk woman, named Anahareo, with whom he lived. After Grey Owl had trapped a female beaver from its lodge, Anahareo convinced him to raise the two young beavers left behind. Anahareo loved animals and hated the cruel trapping practices of the frontiersmen.

Grey Owl was captivated by the young beavers and soon became concerned that beavers would become extinct from the heavy trapping that Canada was experiencing to feed an insatiable European market for beaver pelts. He was consumed by the vision that the Canadian wilderness—and the Native People who lived sustainably in it—were doomed unless conservation replaced exploitation. In his forties, Grey Owl began to write extensively about conservation, eventually publishing four books on the subject. His writing was very popular and, in the 1930s, he was arguably Canada’s most famous author and conservationist, compared favorably to John Muir. He lectured widely and produced conservation films. He was especially popular in England, where one lecture tour pulled in a quarter million people. In 1936, he reflected on his work:

“Every word I write, every lecture I have given, or ever will give, were and are to be for the betterment of the Beaver people, all wild life, the Indians and halfbreeds, and for Canada, in whatever small way I may.”

The Canadian government provided him housing and an area to raise beavers for release in Prince Albert National Park, Saskatchewan. Some credit him with saving the beaver—the national animal of Canada—from extirpation.

He died suddenly of pneumonia in 1938, and then the wheels started coming off the story of Grey Owl. Journalists investigated the details of his life—and the truth emerged: Grey Owl was an imposter. He was not half Native American, he had not been born in Mexico.

His real name was Archibald Belaney, born on September 18, 1888, in Hastings, England. His parents—one British and one American—left him to be raised by two maiden aunts in Hastings. From his earliest days, however, he yearned to get away from the stifling society of Hastings and head to the wilderness. He told a young friend that he was going to go to Canada. His friend asked, “To fight the Indians?” Belaney answered, “No, to become an Indian.” At 17, he made his escape, crossing the Atlantic and then disappearing into the forests of northern Canada.

He lived with the Ojibwa People, learning their language and ways. He dyed his hair black and darkened his skin with henna dye. He roamed among various tribes, eventually meeting Anahareo and becoming the committed conservationist that captured the Canadian conscience.

Opinions about Belaney vary, of course. Some see him as a charlatan who stole the Native Peoples’ voice. Others see him as a mixture of good and bad. Clive Webb, at the University of Sussex, proposed that we “separate some of his personal shortcomings from his great work as a conservationist.” And Don Smith, of the University of Calgary, saw him this way:

“This is 1930s Canada, it seemed to have inexhaustible forest. His personal life was a mess but he had insight, he had vision. This man had a message. Everybody’s green now. He was green when there was nothing to it. His message was ‘you belong to nature, it does not belong to you’.”

As the lobbyist said, there are two sides to every pancake. You decide on which side of this man—the conservationist Grey Owl or the imposter Archibald Belaney—you’d like to pour your syrup.

References:

Brower, Kenneth. 1990. Grey Owl. The Atlantic online, January, 1990. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/90jan/greyowl.htm. Accessed June 10, 2019.

Howes, David, and Constance Classen. Grey Owl, White Indian. Canadian Icon. Available at: http://canadianicon.org/table-of-contents/grey-owl-white-indian/. Accessed June 10, 2019.

Onyanga-Omara, Jane. 2013. Grey Owl: Canada’s great conservationist and imposter. BBC News, 19 September 2013. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-sussex-24127514. Accessed June 10, 2019.

Smith, Donald B. 2015. Archibald Belaney, Grey Owl. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/archibald-belaney-grey-owl. Accessed June 10, 2019.