Now here’s a Christmas present that we wish the Grinch would steal and never return—the bunny rabbit. At least that’s the way Australia feels about rabbits. The European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) is not native to Australia, but they may be the most abundant mammal in the country today and certainly the most tragic.

It’s all because of a wealthy English immigrant, Thomas Austin. Austin lived in a rural town in the Australian state of Victoria (in the southeastern corner of the country, where Melbourne is). He missed his native England, including his hobby of hunting small game. He had a good idea, and wrote to his brother asking him to send some rabbits, hares and partridges to release on his property. Austin reasoned that “[t]he introduction of a few rabbits could do little harm and might provide a touch of home, in addition to a spot of hunting.” His shipment arrived, and Austin released his rabbits on December 25, 1859.

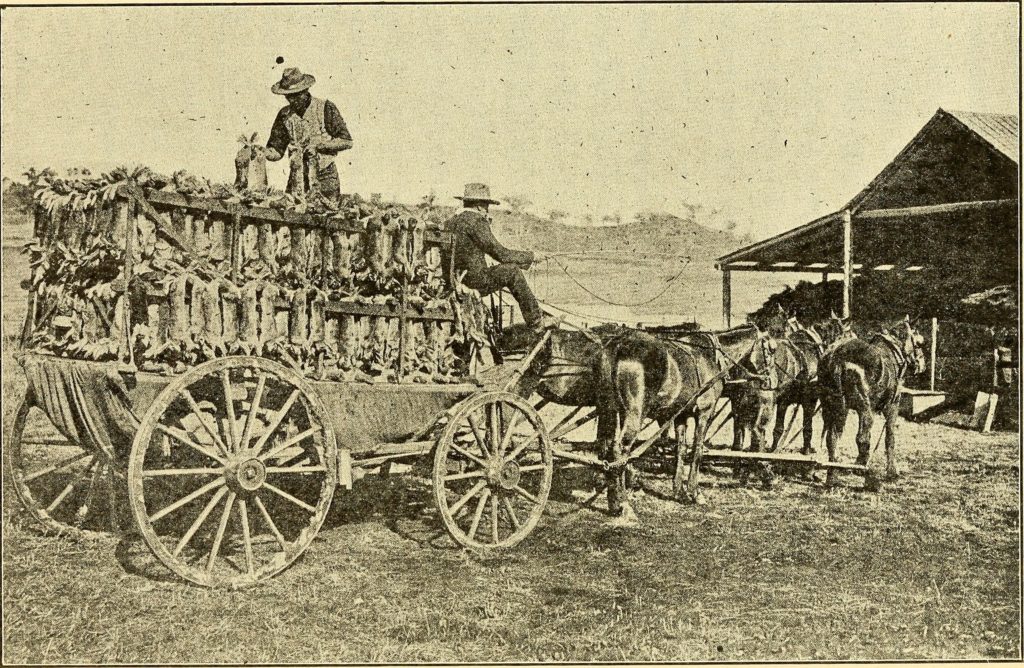

He was right about one thing—they sure did provide some hunting. The few rabbits he released (12-24, reports vary) reproduced like, well, rabbits. In 1866, just 7 years after the release, Austin and his friends were harvested 14,000 rabbits, just from his property!

And the population kept on growing and spreading. Australia was perfect habitat for rabbits. The loose soil allowed easy burrowing of underground dens, called warrens. Sparse tree cover allowed ample growth of ground plants and seedlings, all of which the rabbits devoured with enthusiasm. The rabbits had few native predators, and the mild climate allowed them to breed several times each year. By 1900, rabbits lived up to 3000 miles beyond the release point, and by the 1940s, the total population had reached 600 million (that’s the most conservative estimate; some say the peak was 2 to 10 billion!). Today, rabbits live in all but the most desert-like parts of the country. The invasion of Australia by rabbits is the fastest colonization by any mammal in history.

But Austin was wrong about another thing. Rabbits could cause harm—and have, lots of it. Overgrazing by dense rabbit populations has reduced vegetation on the land, as the voracious herbivores ate virtually all shoots and seedlings of grasses, shrubs and trees, putting several native species on the path to extinction. With the vegetation gone, soil erosion increased. Other herbivores couldn’t compete with the huge rabbit population, causing several native bird and mammal species to decline precipitously. All of these changes, along with direct grazing by rabbits on agricultural crops, is said to cost Australia about $200 million annually.

Australia has tried about everything to control rabbits. Hunters tried, but they couldn’t keep up with the rabbit’s ability to reproduce. Next came fencing. In the late 1800s, building rabbit-proof fences was a national priority. The longest fence ran about 2,000 miles, north to south, to protect Western Australia from invasion (it didn’t work). At one time, there were nearly 200,000 miles of rabbit fences in Australia. Fences, however, are imperfect barriers, expensive to build and requiring constant maintenance. Another physical attack has been digging up active warrens, destroying the nesting and sheltering ability of rabbits

Next came biological control. Scientists introduced myxomatosis, a virus that targets rabbits, in the 1950s. It worked well, but rabbits quickly developed immunity (about half of the population remains immune). A second virus—rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus, or calicivirus—took over in the late 1990s. It has been highly effective, but resistance has cropped up in recent years.

Altogether, these tactics have reduced the rabbit population to about 200 million individuals. That’s still a lot of rabbits, but Australia is a big place. The reduction has allowed several species of small mammals to resurge, especially in the driest regions. With fewer rabbits, introduced feral predators such as cats and foxes are also declining. The dusky hopping mouse, plains mouse and crest-tailed mulgara—all sensitive species that had declined—are now thriving.

Nevertheless, the lesson is clear: just because a species is tasty, cuddly or pretty back home doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to take it along when you move. Better to let nature, not nostalgia, make those judgments.

References:

Australian Government. Feral European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Available at: https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/7ba1c152-7eba-4dc0-a635-2a2c17bcd794/files/rabbit.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2020.

Goldfarb, Ben. 2016. A virus is taming Australia’s bunny menace, and giving endangered species new life. AAAS Science, Feb 17, 2016. Available at: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/02/virus-taming-australia-s-bunny-menace-and-giving-endangered-species-new-life. Accessed January 9, 2020.

National Museum of Australia. Rabbits introduced. Available at: https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/rabbits-introduced. Accessed January 9, 2020.

Oster, Grant. 2014. Thomas Austin and His Rascally Rabbits. Hankering for History. Available at: https://hankeringforhistory.com/thomas-austin-and-his-rascally-rabbits/. Accessed January 9, 2020.

Rabbit Free Australia. Controlling Rabbits. Available at: http://www.rabbitfreeaustralia.com.au/rabbits/controlling-rabbits/. Accessed January 9, 2020.