By Royal Assent of the government of Australia, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park was created on June 20, 1975. The act stated that its purpose was “to provide for the long term protection and conservation of the environment, biodiversity and heritage values of the Great Barrier Reef Region.”

And it is a “region,” often described as the world’s largest living structure. The area included in the park is about half the size of Texas, or about the size of Germany. The reef system stretches along the northeastern coast of Australia for about 1400 miles, making it 8 times longer than the world’s second longest reef (in Belize). The park itself extends from shore into the sea, up to 150 miles at its widest. The park specifically also includes the airspace above and the seafloor below the reef itself.

The size is matched by the amount of biodiversity. Ecosystems include 3000 coral reefs and about 1000 islands of various origin—land, coral and mangrove. Those ecosystems are inhabited by an immense variety of species—600 corals, 100 jellyfish, 3000 mollusks, 500 annelids, more than 1700 fish and 30 marine mammals.

The park itself is what IUCN calls a “managed resource area.” Rather than the type of total protection provided by typical U.S. national parks, the Great Barrier Reef is managed in zones. Some zones are totally protected but others are available for commercial and aboriginal fishing, commercial tourism and as transportation corridors for port cities within the region .

Despite its protected status, the reef has been subject to negative impacts through time. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Area, but in 2012, a special report by UNESCO indicated that it required more protection to retain that designation. In response, the Australian government strengthened protection against transportation damage and siltation from poor land use practices on adjacent shore areas. In 2015, the government announced the elimination of ongoing dredging operations, restriction on new port development and transportation corridors and allocation of $2 billion for restoration and protection. The Reef 2050 Plan calls for a 50% reduction in sediment loads by 2025.

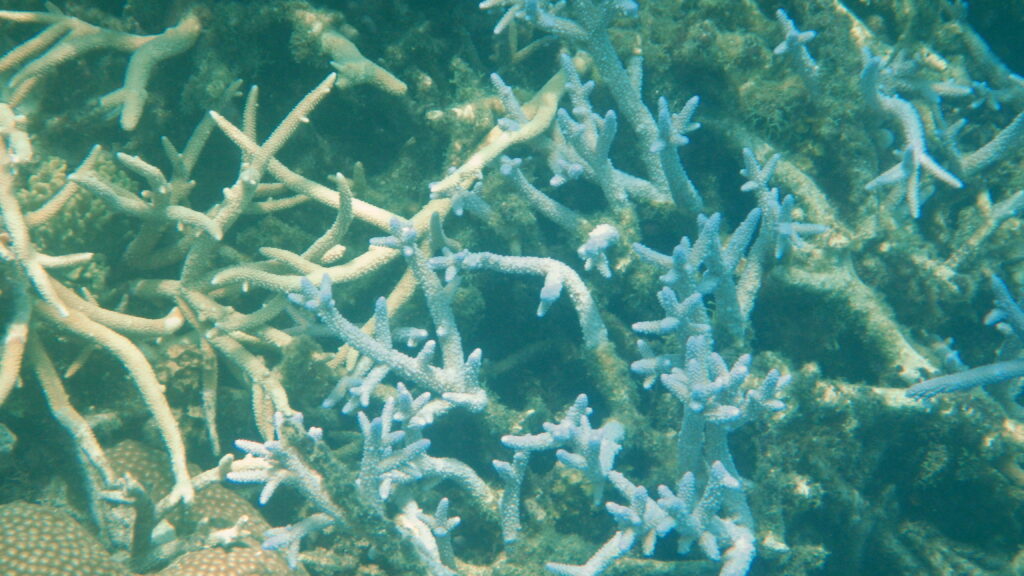

Climate change has also affected the Great Barrier Reef. Long periods of exposure to warm water can kill coral animals, a process known as coral bleaching. Reefs usually recover from bleaching events, but the recolonization process can take decades. If warm-water events recur frequently, the damage can become irreversible. Record high temperatures caused consecutive bleaching events in 2016 and 2017, damaging large areas of the reef. Estimates suggest that up to one-third of shallow-water corals may have been killed on the northern reef.

References:

Commonwealth of Australia. 2015. State party report on the state of conservation of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (Australia). Available at: http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/cb36afd7-7f52-468a-9d69-a6bdd7da156b/files/gbr-state-party-report-2015.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2017.

Commonwealth Consolidated Acts. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975-Sect 2A. Available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/gbrmpa1975257/s2a.html. Accessed June 21, 2017.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Facts about the Great Barrier Reef. Available at: http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/about-the-reef/facts-about-the-great-barrier-reef. Accessed June 21, 2017.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Managing the Reef. Available at: http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/managing-the-reef. Accessed June 21, 2017.

Greening Australia. Improving the health of the Great Barrier Reef—Reef Aid. Available at: https://www.greeningaustralia.org.au/project/Great-Barrier-Reef. Accessed June 21, 2017.

Hoggenboom, Mia. 2016. How will the Barrier Reef recover from the death of one-third of its northern corals? The Conversation AU, May 30, 2016. Available at: https://theconversation.com/how-will-the-barrier-reef-recover-from-the-death-of-one-third-of-its-northern-corals-60186. Accessed June 21, 2017.