We remember Aldo Leopold as the “father of wildlife conservation,” but we could just as easily recognize him as the father of wilderness. Leopold’s foresight and vision led him to propose that a new concept—wilderness—be carved out of America’s national lands.

Aldo Leopold was a forester by training, and his first professional job was on the national forests of New Mexico. From 1909 to 1924, he worked his way up the ranks, eventually becoming the Chief of Operations for the Albuquerque District of the US Forest Service. The biggest part of his job was to perform long field observations of the district’s forests, assessing their conditions and making recommendations for improvements (learn more about Leopold here).

On his field inspections, he observed a troubling trend, “the domestication of the landscape.” In order to provide for the many uses of national forests, roads were being extended deep into the forests, along with the accompanying power and phone lines, buildings and people. Even from a recreational perspective, Leopold objected: “It is just as unwise to devote 100 percent of the recreational resources of our public parks and forests to motorists as it would be to devote 100 percent of our city parks to merry-go-rounds.”

Instead, he believed a portion of the landscape should be left without human development. Undeveloped land was a storehouse for natural diversity, providing knowledge about ecological processes and habitat for wild species that didn’t fare well around humans. Wilderness, he argued, was also a “product” of the forest, just as were trees and hunted game. Leopold had written the first professional article about wilderness areas in 1921, and three years later he proposed to his supervisors that the Forest Service act on that idea.

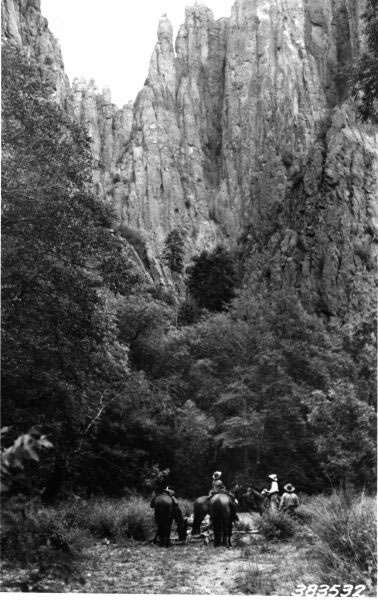

And he knew the perfect place—the Gila National Forest. The sprawling forest in western New Mexico had been impacted less than other forests because of its imposing terrain. In the Gila, the Rocky and Sierra Madre Mountains meet, forming a complex mix of forested mountains, mesas and canyons linked by broad grasslands and deserts. The district forester agreed, and on June 3, 1924, he signed the Gila Wilderness Area into existence—the first such designation in the world.

Since then, of course, many more wilderness areas have been created—today the U.S. has 803 wilderness areas covering over 111 million acres (about 4.5% of the country). The Gila is the largest in New Mexico, covering about 560,000 acres. The Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area is adjacent to the Gila on the East, adding another 200,000 acres to form a contiguous area as large as Rhode Island. All wilderness areas are now protected under The Wilderness Act, passed in 1964 (learn more about the Wilderness Act here). Wilderness areas are managed by the land management agency in whose lands they lie—the National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or U.S. Forest Service.

The Gila is a nature lover’s paradise. It is a crossroads of ecosystems, with an expansive biodiversity. The forests range from pinion-pine-juniper stands on the east to ponderosa pine in the central portion and spruce-fir areas on the higher-elevation west. The fauna ranges from elk to Gila monsters, and several packs of re-introduced Mexican wolves call the Gila home. As Tim Gibbons wrote, on the Gila “you can hook a catfish on one cast and the endemic Gila trout on another.” Trails wind 800 miles through the landscape (not sure Leopold would like that), but are accessible only on foot or horseback.

So, not only must be thank Aldo Leopold for the conservation philosophy he wrote in Sand County Almanac and the technical ideas he developed for wildlife management, but also for starting us on the path to preserving wilderness. Bravo, Aldo!

References:

Gibbons, Tim. 2014. An American Original: Aldo Leopold in the Gila Wilderness. Your National Forests Magazine, Summer/Fall 2014. Available at: https://www.nationalforests.org/our-forests/your-national-forests-magazine/aldo-leopold-in-the-gila-wilderness. Accessed March 13, 2020.

Nielsen, Larry A. 2017. Nature’s Allies – 8 Conservationists Who Changed Our World. Island Press, Washington, DC. 255 pages.

US Forest Service. History of the Gila Wilderness. Available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/gila/learning/history-culture/?cid=stelprdb5038907. Accessed March 13, 2020.

Wilderness Connect. Gila Wilderness; and Fast Facts. Available at: https://wilderness.net/visit-wilderness/?ID=205. Accessed March 13, 2020.