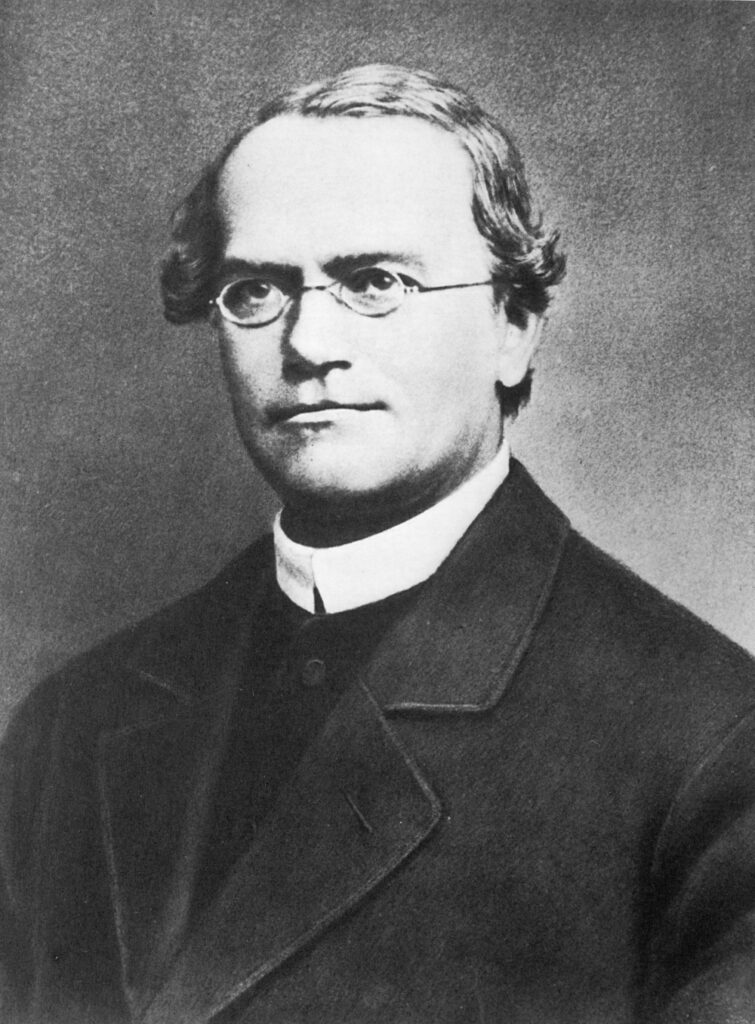

Gregor Mendel, the father of modern genetics, was born on July 20, 1822 (died 1884). Mendel grew on a family farm in what is now The Czech Republic. His home was then part of Austria, so he is generally described as an “Austrian monk.” His farm background made him familiar with plants and the way they changed over time—the basis for his experiments in heredity that have made his name an easy to answer trivia question.

Mendel was an excellent pupil in early schooling and, therefore, was encouraged to continue on in school. As well as studying science, he pursued the ministry, becoming a Catholic monk in his mid-20s. He settled into a life of study and research at the St. Thomas Monastery in Brno (now also in The Czech Republic).

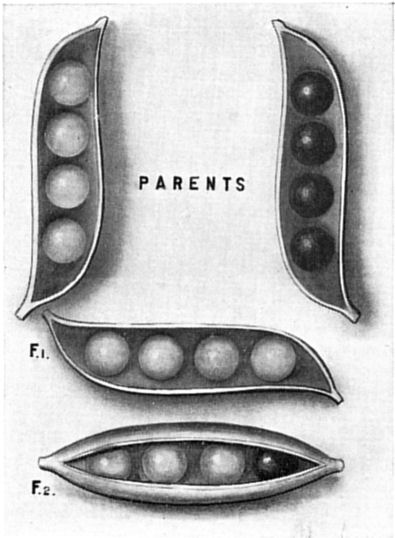

At Brno, he began experimenting with the way traits were passed down from one generation to the next. He used pea plants as his subject, because peas were grown in the monastery’s garden and because they had several traits that were easy to observe, like color of the peas, and grew to maturity rapidly, allowing his experiments to proceed rapidly.

He grew tens of thousands of pea plants between 1856 and 1863. From what he observed in generation after generation of traits, he deduced that plants had both dominant and recessive traits (green peas were dominant, yellow peas recessive) and that those traits were randomly passed on to the next generation. Today we know the mechanism—genes—that Mendel could only hypothesize.

In 1865, the Natural Science Society of Brno published papers by Mendel that described his data and ideas. While I’d like to write that Mendel and his results “went viral,” the opposite happened. He was ignored. The data and ideas were too complicated, and leading scientists doubted that what he observed was universal.

Mendel had other things to worry about. He was appointed Abbot of the monastery just a few years later, a job that absorbed all his time. His eyesight began to fail, preventing further scientific work. He died in 1894, at age 61.

Despite his work being ignored, Mendel was correct. At the start of the 20th Century, three other botanists duplicated his work and published the results again, eventually giving Mendel credit for the original discovery.

The understanding of how variations in nature are passed from generation to generation is crucial to the understanding of biodiversity and, hence, to conservation. For example, we now know that a large pool of genetic diversity is essential for a species to remain adaptable to changing environmental conditions, whether caused naturally or by humans. Scientists working to reproduce endangered species in captivity must track genetic diversity so that the adaptability of new individuals and populations isn’t compromised.

As conservationists work to maintain endangered species or to re-introduce populations into the wild, the concepts of Mendelian genetics are always part of the strategies. And for this reason, Gregor Mendel is as important to our history as are Charles Darwin, E. O. Wilson and Rachel Carson.

References:

Biography.com. Gregor Mendel—Botanists, Scientist (1822-1884). Available at: https://www.biography.com/people/gregor-mendel-39282. Accessed July 20, 2017.

Miko, I. 2008. Gregor Mendel and the principles of inheritance. Nature Education 1(1):134. Available at: https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/gregor-mendel-and-the-principles-of-inheritance-593. Accessed July 20, 2017.

National Institutes of Health, Office of History. Gregor Mendel: The Father of Modern Genetics. Available at: https://history.nih.gov/exhibits/nirenberg/hs1_mendel.htm. Accessed July 20, 2017.