Things are a lot different today in national parks than they were a century ago. At the turn of the 20th Century, parks had official boundaries, but little else—few or no staff, few roads and other facilities and almost no enforcement of park rules. One man, Charles Young, however, demonstrated that conditions could be different.

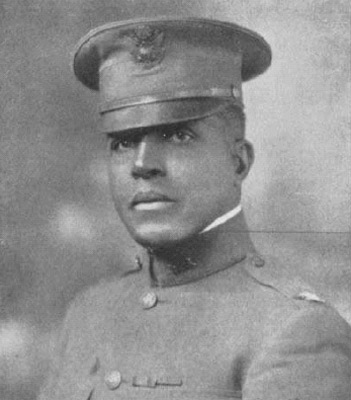

Charles Young was born on March 12, 1864, in Kentucky, the son of former slaves. His family moved across the Ohio River to Ripley, Ohio, where the Emancipation Proclamation had made them free. He attended school there, graduating with honors from the integrated high school in 1881.

He taught high school in his hometown until 1884, when he won admission to West Point. After suffering through academic, isolation and racist struggles, he graduated in 1889, only the third African American to do so. Young went on to a series of assignments in the western United States before being posted as an instructor to the military science program at Wilberforce University, Ohio, in 1894. He taught there for several years, earning a distinguished professorship and adopting Wilberforce as his hometown for the rest of his life.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Young, now a major, returned to regular duty, leading a squadron of Buffalo Soldiers (the nickname of the 9th Cavalry of African American army soldiers) in Cuba. He then became military attache in Haiti, the first American American to hold such a prominent military and diplomatic post.

In 1903, Young achieved another first. At the time, the US Army was responsible for staffing national parks, and Young was named Acting Superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant National Parks (now a part of Kings Canyon National Park), the first African American to serve as a park superintendent. His tenure was short, lasting only from June through November (the usual summer term for such assignments). But whereas other military leaders given such an assignment might consider it a paid vacation, Young was exceptional. Previous detachments had made only minimal progress at the parks, but Young undertook his assignment with energy and commitment. During their stay, Young and his Buffalo Soldiers built more than 15 miles of quality roads and 18 miles of trails—the same pathways still used today by millions of Americans to visit the parks’ giant sequoias, the largest trees in the world.

Young and his troops also took seriously the laws to protect the parks. They turned back shepherds and their flocks of sheep, previously grazing illegally on park lands. They enforced the prohibition on hunting, with no poaching violations reported during their tenure. Noting that some of the largest and most accessible trees were suffering from over-visitation, they built fences around the trees to keep the visitors at a distance. The local community was so pleased with Young’s accomplishments that they wished to name a tree in his honor, as had been done for other notable Americans. He declined the honor, however, suggesting that a tree be named instead for Booker T. Washington, the great African American educator.

Young returned to active duty after his time in the parks, serving with distinction in the Philippines, Mexico and Liberia. He was the highest-ranking African American in the US Army at the start of World War I, but was forced to retire in 1917 (various accounts suggest that his forced retirement was to avoid his becoming the first African American to achieve the rank of general). After the war, the Army reinstated Young as a colonel. He died while on an assignment in Nigeria in 1922. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Charles Young spent only a short time as an active conservationist, but his role was transformative, not only for the parks he worked in but also as an example that the parks could—and should—be more actively managed and protected. He clearly understood what the parks were about, as he wrote in his final report as Acting Superintendent:

“Indeed, a journey through this park and the Sierra Forest Reserve to the Mount Whitney country will convince even the least thoughtful man of the needfulness of preserving these mountains just as they are, with their clothing of trees, shrubs, rocks, and vines, and of their importance to the valleys below as reservoirs for storage of water for agricultural and domestic purposes. In this, lies the necessity of forest preservation.”

References:

Arlington National Cemetery. Charles Young, Colonel, United States Army. Available at: http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/cdyoung.htm. Accessed January 27, 2021.

National Park Service. Colonel Charles Young. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/chyo/learn/historyculture/colonel-charles-young.htm#CP_JUMP_3401413. Accessed January 27, 2021.

National Park Service. Colonel Charles Young, Early Park Superintendent. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/seki/learn/historyculture/young.htm. Accessed January 27, 2021.