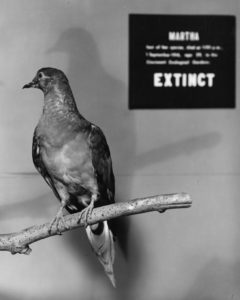

Martha, the last surviving Passenger Pigeon, died on September 1, 1914. Martha had been born in a zoo (Probably Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo) and later was relocated to the Cincinnati Zoo, where she lived until her death. With her death, a species that had once been the single most abundant bird in North America—and probably the world—went extinct.

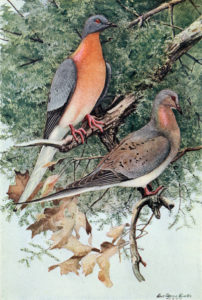

The Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) was most closely related to the Mourning Dove, but almost twice as large. It measured 16 inches long, its large body able to propel it on long flights over vast areas. Flocks of Passenger Pigeons roamed from Canada to the Gulf Coast and from the Atlantic to the western edge of the Midwestern forest landscape. They were communal birds, nesting in large groups with sometimes hundreds of nests in a single tree, so heavy that limbs broke under their weight. What most distinguished Passenger Pigeons, however, were their huge flocks flying around the eastern half of North America. Flocks were often over a mile wide, stretching as far as the eye could see, from horizon to horizon. John Audubon observed a flock a he traveled to Louisville, Kentucky, in 1813:

“The air was literally filled with Pigeons. The light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse, the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow; and the continued buzz of the wings had a tendency to lull my senses to repose.”

When he reached Louisville, the flock was still overhead—and continued passing for another full day. A flock that passed through Ontario in 1860 was estimated to contain more than 3 billion birds, and a nesting colony in Wisconsin included 136 million breeding birds over an 850-square-mile swath of forest. One estimate suggests that as many as 40% of all birds in North America were Passenger Pigeons.

The habit of the birds to fly in such huge flocks made them vulnerable to uncontrolled exploitation. They were shot and trapped for food—the birds were meaty and delicious—both by individuals and by commercial hunters. As their natural forest habitats were converted to farmlands, they were shot because they fed on crops. That a species so abundant could be overharvested was unimaginable, but by the late 1800s, only isolated colonies existed. By 1890, the Passenger Pigeon had all but disappeared from the wild. Three captive populations at the Chicago, Milwaukee and Cincinnati Zoos gradually died out.

Martha, named after the nation’s first First Lady, lived to the ripe old age of 29 in her comfortable zoo environment. A $1,000 reward was offered to anyone who could find a male to breed with Martha—but no mate was ever found. She grew weaker over the years, to the point that zookeepers lowered her perch to just a few inches off the ground so she could hop up rather than fly. When she died on September 1, 1914, her body was immediately packed in a huge block of ice and sent to the Smithsonian Institution for mounting.

One century of unbridled exploitation and massive habitat changes had doomed the world’s most abundant bird to extinction—a sobering reminder of the need for conservation.

References:

Harvey, Chelsea and Elizabeth Newbern. 2014. 13 Memories of Martha, the Last Passenger Pigeon. Audubon, August 29, 2014. Available at: http://www.audubon.org/news/13-memories-martha-last-passenger-pigeon. Accessed August 31, 2017.

Smithsonian. “Martha,” The Last Passenger Pigeon. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Explore Our Collections. Available at: https://naturalhistory.si.edu/onehundredyears/featured_objects/martha2.html. Accessed August 31, 2017.

Smithsonian. The Passenger Pigeon. Encyclopedia Smithsonian. Available at: https://www.si.edu/encyclopedia_si/nmnh/passpig.htm. Accessed August 31, 2017.

Souder, William 2014. 100 Years After He Death, Marth, the Last Passenger Pigeon, Still Resonates. Smithsonian Magazine, September 2014. Available at: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/100-years-after-death-martha-last-passenger-pigeon-still-resonates-180952445/. Accessed August 31, 2017.