Want to start an argument about how to produce electricity without climate change? Bring up nuclear energy (and at this moment in 2022, that argument just got more interesting with news that a major breakthrough in nuclear fusion has been achieved). Want to start an argument about the history of nuclear energy among a bunch of nuclear dudes? Just ask which was the first nuclear energy plant!

But for our purposes today, we’re going with the Shippingport Atomic Power Station in western Pennsylvania (don’t look for it on a map, because it is gone). Several candidates for the title of “first” exist, depending on the qualifiers used, but it appears that Shippingport may have been the first “full-scale” commercial plant built solely to produce electricity. It was fired up on December 2 and started sending electricity through the power grid on December 18, 1957.

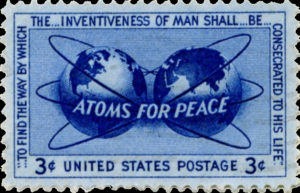

Shippingport only got there by accident. When the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end World War 2, the public was deadly scared of what the world’s capacity to harness atomic energy might mean; the arms race and the cold war resulted. But U.S. President David Eisenhower had a different idea—to use the power of atoms to create energy. He called his idea “Atoms for Peace,” and directed U.S. federal agencies to get cracking on ways to use atoms in other ways.

Consequently, a new atomic age began. The U.S. started building atom-fueled navy ships, especially aircraft carriers. While the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) developing a nuclear reactor for a new aircraft carrier, Congress decided it was too expensive and took away the funding. With a partially built nuclear reactor, the AEC quickly changed strategies—let’s turn it into a commercial nuclear energy plant, producing electricity for the country. President Eisenhower agreed and he assigned Admiral Rickover to manage the process (Rickover is known as the “Father of the Atomic Navy”). The AEC chose Shippingport, Pennsylvania, on the Ohio River west of Pittsburgh, as the location, and Rickover got it built, pronto. His biographer noted:

“Commercial nuclear power was now a reality, just four and a half years after the task was assigned to Admiral Rickover. Three years later, commercial plants based on this design began to spring up across the country, and shortly after that, around the whole world.”

Indeed, nuclear energy has expanded around the country and world. Today, 99 nuclear reactors produce electricity in 30 U.S. states, supplying 20% of the nation’s electricity. The U.S. has more nuclear reactors and capacity than any other country in the world (surprised by that, aren’t you?). France is next with 58, then Japan (42), China (39) and Russia (37). But nuclear energy provides a much higher proportion of all electricity in other countries than in the U.S.—France gets 72% from nuclear, Belgium gets 50%, and Sweden gets 40%. The UK is about tied with the U.S. at 19%. Worldwide, about 450 nuclear reactors produce about 11% of all electricity.

After the spectacular nuclear disaster at Fukushima, Japan, several countries declared a divorce from nuclear energy. Japan itself has lowered its reliance on nuclear from 30% of all electricity to just 4% today. Germany is supposedly phasing out all its nuclear energy capacity, needing to find a replacement source for the 12% of electricity that nuclear provides. The U.S. has only opened one new nuclear facility since 1996, with two more under construction now. But this won’t increase capacity, as older plants are taken off-line.

Other parts of the world, however, are developing nuclear capacity as an alternative to air-polluting fossil-fuel facilities (the major fuel being displaced is coal). In early 2018, 58 nuclear reactors were under construction. Twenty of those were in China alone, followed by 6 each in India and Russia. Many European countries are building new reactors to replace aging or retired reactors.

“Retirement” was the fate of the Shippingport plant. After the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear disaster—also in Pennsylvania—public opinion turned against nuclear energy. In 1982, the plant quit producing electricity, and by 1989 the entire facility was totally gone. Both the accident-free operation of the plant for 25 years and its decommissioning are used as examples of how well nuclear energy can work.

Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on your view), nuclear energy has a target on its back. Nuclear energy is the safest of all methods of producing electricity (deaths per kilowatt hour generated), and nuclear plants operate more reliably and much closer to full capacity than fossil-fuel plants. And depending on how you do the math, nuclear energy doesn’t generate greenhouse gases (when the fossil-fuel energy consumed by mining of materials and construction of reactors is included, there is a net contribution of greenhouse gases—just like all power plants). But spectacular accidents like Fukushima, Chernobyl and Three Mile Island drive policymakers and the public against nuclear energy. And the safety of long-term storage of radioactive wastes is a chronic worry that can’t be explained away.

But here is the question that we all must consider: From what source do you wish to get your electricity? It is not an easy question, and, regardless of individual answers, it is clear that nuclear power plants will be part of our global energy future for a long, long time.

References:

Craddock, Jack III. 2016. The Shippingport Atomic Power Station. Standford University. Available at: http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2016/ph241/craddock1/. Accessed December 5, 2018.

Energy Information Administration. Nuclear Explaned—U.S. Nuclear Industry. Available at: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/index.php?page=nuclear_use. Accessed December 5, 2018.

Statista. 2018. Number of under construction nuclear reactors worldwide as of February, 2018. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/513671/number-of-under-construction-nuclear-reactors-worldwide/. Accessed December 5, 2018.

World Nuclear Organization. 2018. Nuclear Power in the World Today. Available at: http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/nuclear-power-in-the-world-today.aspx. Accessed December 5, 2018.