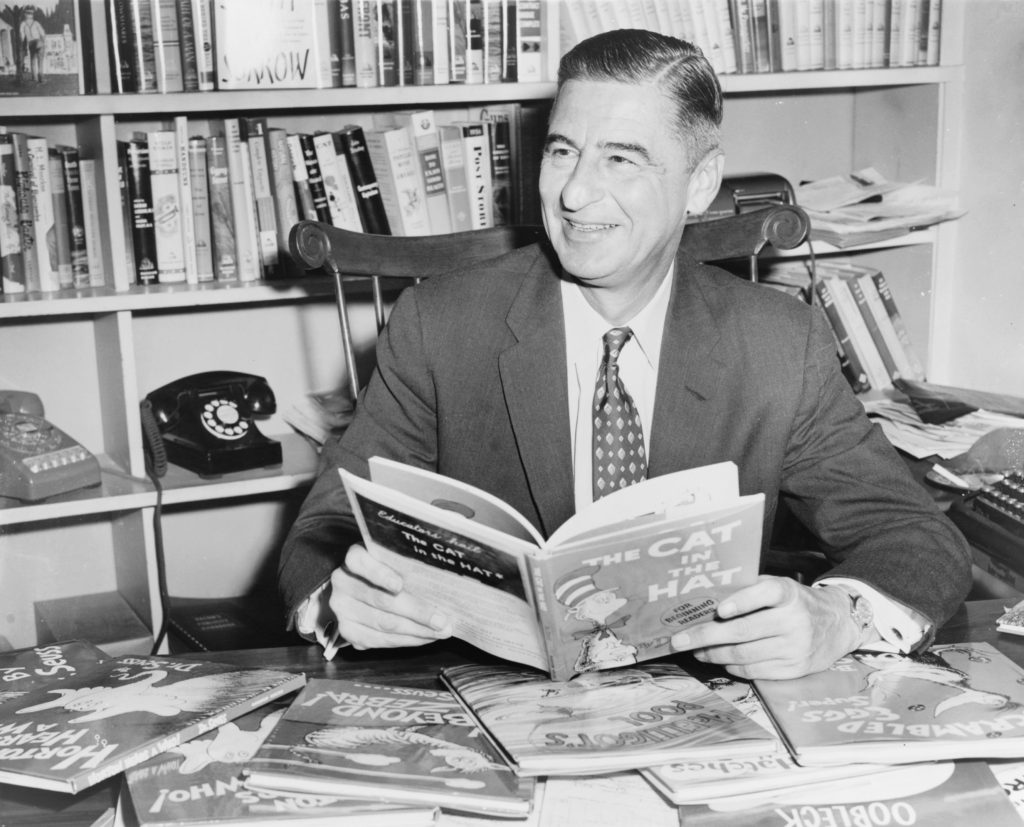

March 2 belongs to Dr. Seuss. Theodore Geisel, who became famous as the author Dr. Seuss, was born on March 2, 1904 (died 1991). He became the world’s most famous children’s author, writing and usually illustrating more than 60 books that have sold more than 600 million copies and been translated into more than 20 languages.

Ted Geisel adopted the name Seuss as a college student, to allow him to continue drawing cartoons for his college’s humor magazine after university administrators kicked him off the staff. Seuss is his mother’s maiden name and his middle name. He later added Dr. to his pseudonym to give it more of an authoritative air.

Before he became a writer of children’s book, Dr. Seuss was a cartoonist. In the 1930s, he drew advertising cartoons. Most notable was a series for the insecticide Flit, a product of Standard Oil. The ads always included the line, “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” The line became a common idiom for seeking help in an emergency. When Geisel began to write books, he turned to children’s books, he said, because it was the only writing that his contract with Standard Oil would allow.

The world has benefitted from that clause in his contract. Geisel’s simple rhymes, repetitive themes, and fantastic drawings are as familiar as they are strange. But often hidden within those simple books are profound messages. The Sneetches taught tolerance for those who are different. Yertle the Turtle warned against tyranny. Horton Hears a Who teaches us to stand up for the weak.

For conservation, we have no better textbook than The Lorax. Geisel published The Lorax in 1971, at the height of American’s emerging concern for the environment. The Lorax tells the story of the Once-ler, who exploited the magnificent Truffula Tree and other resources at the far edge of town. The Lorax warned the Once-ler to be careful, not to overdo his harvests. But, pushed by greed and the insatiable markets for Thneed made from Truffula Trees, the Once-ler ignored the warnings. Gradually, the trees and all the resources depending on them—like Bar-ba-loots and Humming-Fish—disappeared. The Lorax departs, too, leaving a forlorn Once-ler to live alone in a gray and hopeless world (more about the book here).

The message of the book is clearly conservationist, not preservationist. But some people did not see it that way. In the logging communities of the Pacific Northwest, the book was banned from public libraries. The lumber industry put out a pro-logging response in its own children’s book, The Truax. Notably, however, neither the Lorax nor Geisel was against using trees or forests, just against over-using them. As Geisel said, “The Lorax doesn’t say lumbering is immoral. I live in a house made of wood and write books printed on paper. It’s a book about going easy on what we’ve got. It’s anti-pollution and anti-greed.”

The Lorax may speak literally for the trees, but it speaks figuratively for our need to sustain the wonderful natural resources on which we depend.

References:

Ayers, Kyle. 2012. The Environmental Message Behind “The Lorax.” Available at: http://newyork.cbslocal.com/2012/04/09/the-environmental-message-behind-the-lorax/.

EarlyMoments.com. The Life and Times of Dr. Seuss. Available at: https://www.earlymoments.com/dr-seuss/The-Life-and-Times-of-Dr-Seuss/.

Nel, Philip. Biography of Dr. Seuss. Available at: http://www.seussville.com/#/author.