Several of the people highlighted in this conservation calendar have earned names like “father of conservation,” or “godmother of sustainability.” But in my mind, only one of these father or mother figures stands out as so astoundingly worthy of such a name. His name is Norman Borlaug, known as the “Father of the Green Revolution.”

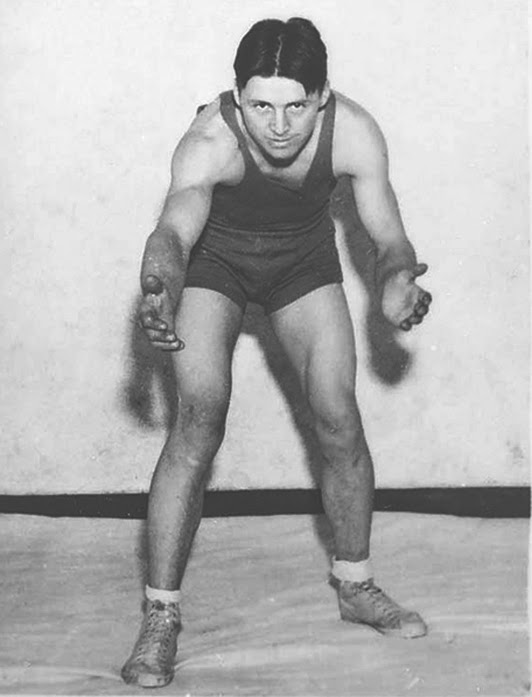

Norman Borlaug was born in 1914 in a small town of northeastern Iowa. He was the son of Norwegian immigrant farmers. Like his neighbors and friends, he worked hard to help his family on the farm and also worked hard in school. He was a strong, active boy who took to wrestling as a sport. As a forestry student at the University of Minnesota, he also wrestled competitively (and eventually was inducted into the NCAA Wrestling Hall of Fame).

But wrestling with the world’s food issues became his fundamental fight. Although he loved forestry—and the nature that it allowed him to enjoy—he switched to studying plant pathology as a graduate student, captured by the possibility of fighting against famine. He graduated in 1942 with a Ph.D. in agronomy, and shortly thereafter was hired as part of a Rockefeller Foundation program to improve wheat yields in Mexico.

For the next 15 years, Borlaug and his colleagues labored to develop better wheat. First they developed strains resistant to diseases like “rust,” then added drought resistance and higher production. But the plants grew so well—tall and full of grain heavy heads—that the stems collapsed from the weight. So, they cross-bred their strains with dwarf varieties from Japan. The results were spectacular. Mexico went from producing half the wheat they needed to satisfying all their domestic needs and exporting food to other nations.

Borlaug had become famous in the developing world for his leadership in transforming agricultural production. He was an unstoppable force in the field, never daunted by the amount or difficulty of the work, scientifically or physically. He overcame the reluctance of local farmers for new ideas, as he learned their language and their culture. He navigated political processes with honesty and integrity. With the success of his work in Mexico, he was asked to produce the same miracles elsewhere, and he did so—in Asia, the Middle East and, with less success, Africa.

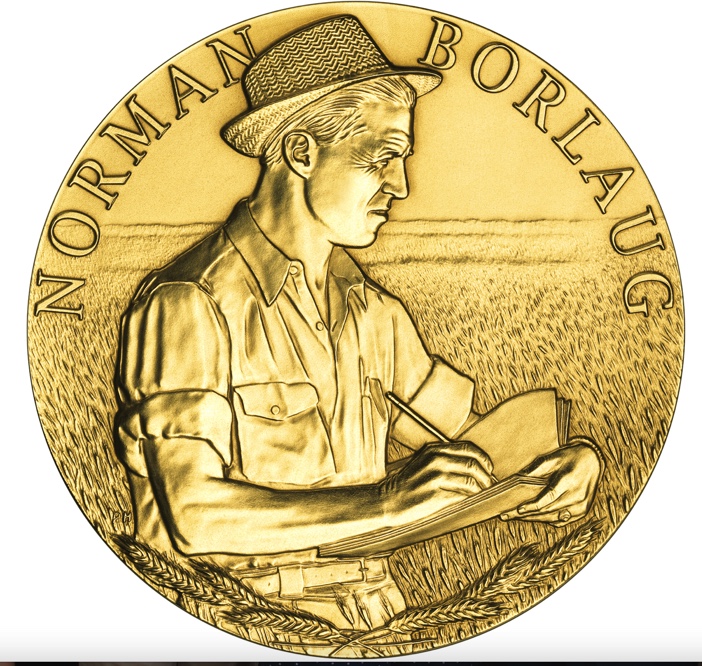

For his efforts, Norman Borlaug became known as the “father of the green revolution.” The green revolution was an entirely new approach to agriculture that used all aspects of modern technology to enhance production. First came improved hybrids, but Borlaug recognized the importance of other aspects as well, including irrigation, fertilization, pest control and the availability of good rural roads. The transformation of agriculture in these ways eliminated the famines that had plagued the developing world.

In 1970, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Borlaug’s selection was the first to recognize that peace was not possible if people were starving and if their environment was not sustainable. He is credited with saving over 1 billion lives. Let that sink in for a moment. 1 billion lives. At the Nobel ceremony, he was recognized as the “indomitable man who fought rust and red tape…[and] who more than any other single man of our age, has provided bread for the hungry world.” He has received similar recognitions from many countries, including the US. Medal of Freedom, our country’s highest civilian award.

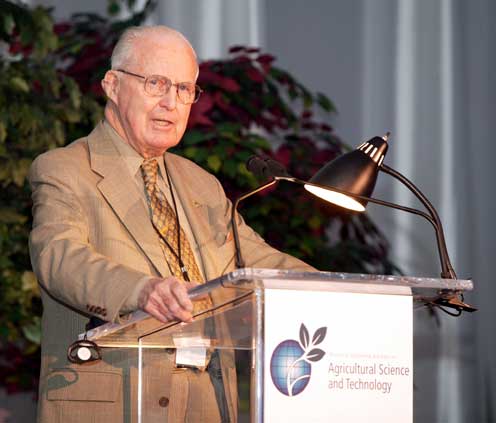

Norman Borlaug never forgot that the base of this success was pragmatism—putting science to work to improve people’s lives (he had no interest in pursuing “academic butterflies”). And he never stopped working directly to help people. When his Nobel Prize was announced, he was deep in a wheat field in rural Mexico. His wife drove an hour to find him and bring him back to take calls from reporters. Sorry, he said, he and his crew were in the middle of recording data, and he went back to work. Eventually, the reporters found him—still at work in the field.

I met Norman Borlaug about the time he was turning 90. He came to North Carolina State University to speak. Between speeches, we thought he should meet with university leaders, or at least take a rest. He wasn’t interested in either. He wanted to meet students. We took him to a middle school, so he could talk to young people about becoming scientists to help the world.

Although Wangari Maathai (learn more about her here) is lauded as the first environmentalist to win the Nobel Peace Prize (and I often say that, too), I think it more accurate to cite Normal Borlaug for that honor. He loved nature, but he knew that nature could not be maintained in a world of hungry people. Today, we call that sustainability. Borlaug said,

“To this day, I enjoy nature, the luxury of undisturbed wilderness, forests, mountains, lakes, rivers and deserts and their wildlife. But I also know that the greatest danger to their perpetuity is the pressure of human population.”

Let that sink in, too.

References:

Nobel Prize Organization. Norman Borlaug, Biographical. Available at: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1970/borlaug/biographical/. Accessed March 14, 2019.

Quinn, Kenneth. M. 2008. Norman Borlaug, Extended Biography. World Food Prize Organization. Available at: https://www.worldfoodprize.org/index.cfm?nodeID=87449&audienceID=1. Accessed March 14, 2019.

University of Minnesota. The significance of Borlaug. Available at: https://borlaug.cfans.umn.edu/unparalleled-achievements. Accessed March 14, 2019.