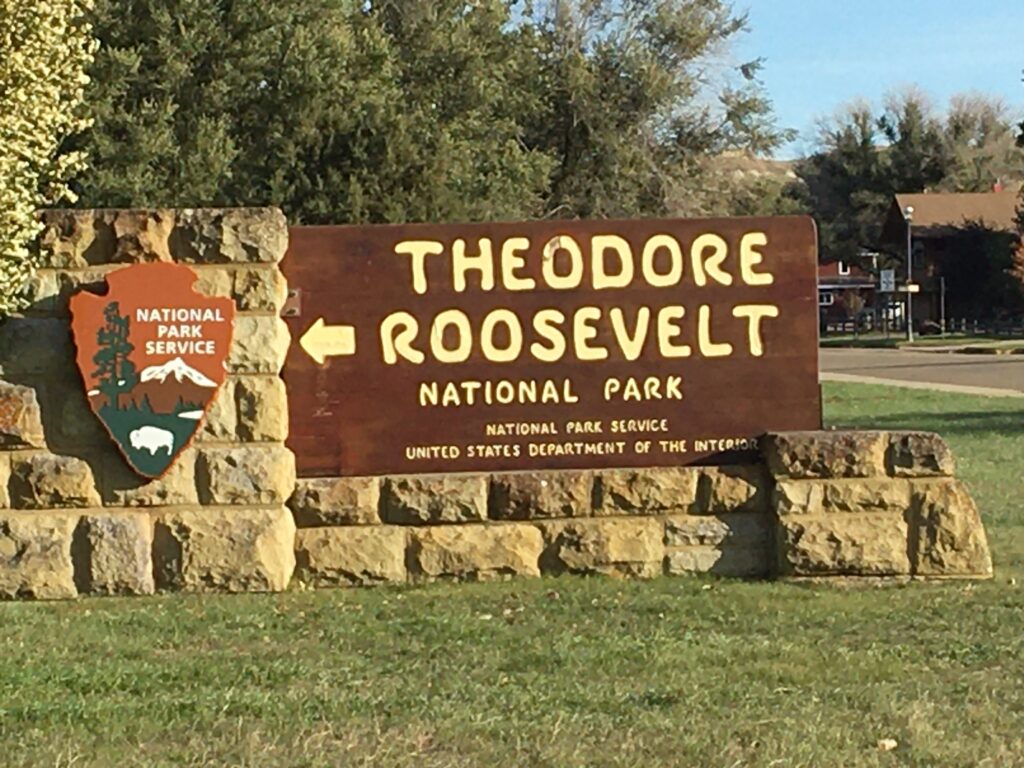

When Teddy Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States, died on January 6, 1919, it wasn’t long before conservationists began advocating for a park in his name. Roosevelt was, after all, our “conservation president,” a leader who established 150 national forests, 51 federal bird reserves, 4 national game preserves, 5 national parks and 18 national monuments encompassing 230 million acres in all. But it did not prove easy to get a park named for him.

As a young man, Roosevelt traveled to the Dakota Territory for a hunting trip in 1883. He fell in love with the land and with the idea of being a rancher. That year, he bought one ranch and a second one the next year. For the next several years, he visited the area often to manage his ranches and enjoy the western lifestyle. The work toughened him and convinced him that he could do anything. “I never would have been President if it had not been for my experiences in North Dakota,” Roosevelt said later.

It seemed logical, then, that a park dedicated to Roosevelt’s conservation heritage be created in North Dakota. In 1921, North Dakota asked Congress to create such a park, and by 1924 a park association formed in the state to promote the idea. The National Park Service didn’t think the area deserved a national park, but agreed, in 1928, to propose a small national monument as a tribute to Roosevelt. Some action began in the 1930s, when the same extended drought that created the Dust Bowl (learn more about the Dust Bowl here) caused North Dakota farmers and ranchers to abandon their lands. The U.S. government bought back millions of acres and created the Little Missouri National Grasslands on the North Dakota-Montana border.

A portion of the grasslands was put into a cooperative park venture among several federal and state agencies, and, by 1935, a Roosevelt Recreation Demonstration Area was established. But when a permanent home for a park was sought, neither the State of Nork Dakota nor the National Park Service wanted to take responsibility. After World War 2 ended, the National Park Service again declined to take on the property, declaring that it was not worthy of national park status. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service ended up with the land, designating it a national wildlife refuge. But with the aggressive and persistent lobbying of North Dakota Congressman William Lemke, Congress passed and President Truman signed, on April 25, 1947, a law creating Theodore Roosevelt National Memorial Park. Thirty-one years later, on November 10, 1978, President Carter signed the law that dropped “memorial” from the name and finally made it official—Teddy Roosevelt finally had his national park, nearly 60 years after his death.

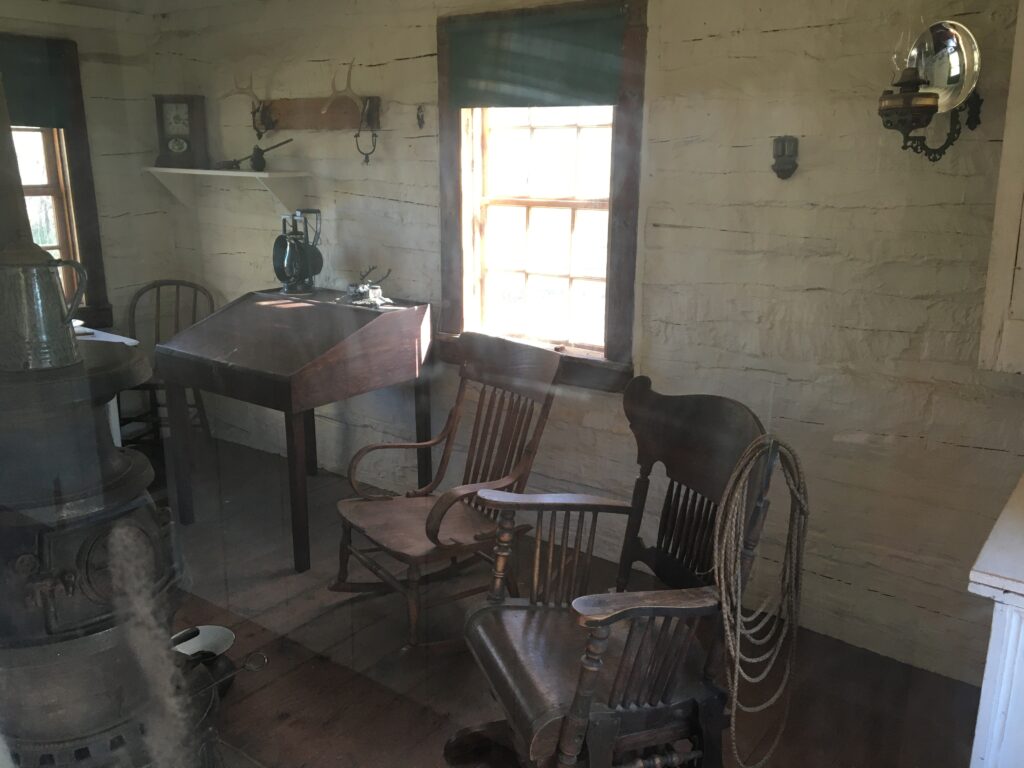

Three separate units comprise the park. The majority of the park’s 70,447 acres are in the South Unit (about 46,000 acres) and North Unit (about 24,000 acres). Between these units is the Elkhorn Ranch Unit of 218 acres, one of the two original ranches owned by Teddy Roosevelt. No area of the park is highly developed, with only primitive campsites, hiking trails and scenic drives, but the Elkhorn unit is kept purposely undeveloped to represent the rugged wildness of Roosevelt’s time. Visitation to the park is relatively low, averaging about 500,000 per year for several decades but recently reaching about 750,000.

The park, therefore, retains the character that Roosevelt loved about the West. It is about nature—rugged, beautiful, an island of solitude. And it reminds us that taking care of such places is a solemn duty. As Roosevelt said in 1910,

“There is a delight in the hardy life of the open. There are no words that can tell the hidden spirit of the wilderness that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy and its charm. The nation behaves well if it treats the natural resources as assets which it must turn over to the next generation increased and not impaired in value.”

References:

National Park Service. Park History, Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/thro/learn/historyculture/park-history.htm. Accessed April 8, 2019.

U.S. Department of the Interior. 2016. The Conservation Legacy of Theodore Roosevelt. USDOI blog, 10/27/2016. Available at: https://www.doi.gov/blog/conservation-legacy-theodore-roosevelt. Accessed April 8, 2019.