According to the website “On This Day,” April 30, 1864 is the date when the first fee for a hunting license was established by the State of New York. I’ve not been able to confirm that event, and usually I wouldn’t validate such a claim with a post if I couldn’t directly verify it from several sources.

But since nothing much else happened in conservation on any April 30, I am going to take the chance that this is a true historical event. Why? Because it gives me a chance to reflect on the importance of hunting and fishing licenses and fees to conservation.

Before getting to the money, however, lets note the reality that hunters and anglers were the first folks who really spoke up for wildlife in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Those who exploited wild game and fish resources recognized that harvests were too high and populations were declining and even disappearing. So, they started talking about it, around the U.S. and around the world, and pressing for government action. Here’s how Teddy Roosevelt put the case:

“In a civilized and cultivated country, wild animals only continue to exist at all when preserved by sportsmen. The excellent people who protest against all hunting, and consider sportsmen as enemies of wildlife, are ignorant of the fact that in reality the genuine sportsman is by all odds the most important factor in keeping the larger and more valuable wild creatures from total extermination.”

They argued for all the conservation tools that we now take for granted: seasons defining when people can fish and hunt; limits on the size and number of animals killed; controls on the kind of equipment that can be used; refuges where animals are free from hunting or fishing; and, perhaps most fundamental, elimination of commercial hunting in the U.S.

Anglers and hunters have always supplied the vast majority of the money spent on fisheries and wildlife conservation, too. Which brings us back to hunting and fishing licenses and fees. Today, every state charges a license fee for the right to hunt and fish. Often the schemes are quite involved, with additional fees for different weapons or rights to capture particular species. Most of the fees are quiet low—much too low, I have always argued—less than the cost of a tank of gas to get from home to the field. Some fees, however, are quite high. In Montana, the fee for non-residents to hunt for a bighorn sheep is $1250. States have collected over $20 billion in licenses and fees since they started, exceeding $1 billion in 2018 alone.

All this money gets put to good use. Fishing and hunting licenses pay about 75% of the budgets of most state fisheries and wildlife agencies. Those agencies don’t just serve anglers and hunters, but all the people of their state. They provide the base protection and management for native biodiversity of all types, whether a butterfly or a bat, and manage millions of acres of lands used by all of us for recreation of all kinds.

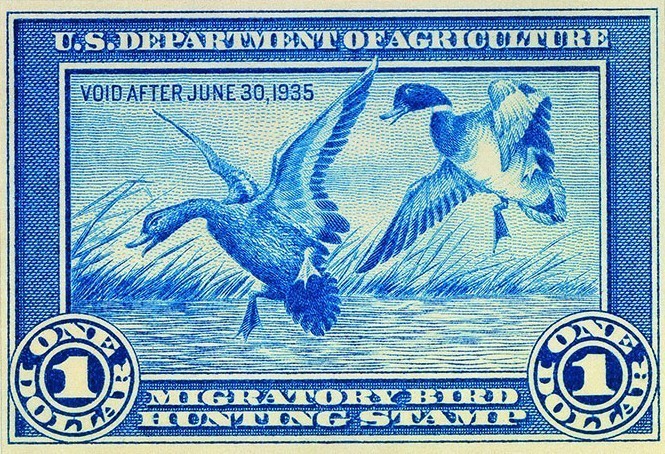

One special kind of license is the federal Duck Stamp. Anyone who hunts for migratory waterfowl—duck, geese, swans and the like—must purchase an annual Duck Stamp (it’s called a “stamp” because it looks like one). The fee when started in 1935 was $1; today a stamp costs $25. The funds from Duck Stamps go to purchase, improve and maintain National Wildlife Refuges. And the program is so efficient that 98 cents of every dollar go directly to this purpose. Since inception, the Duck Stamp program has invested more than $750 million in wildlife refuges.

A hidden fee that hunters and anglers also pay is an excise tax on hunting and fishing equipment. The fees are known after the federal legislators who proposed the law to establish them—Pittman-Robertson for hunting and Dingell-Johnson for fishing. The federal government collects the money—10% of the cost of fishing equipment and 11% of the cost of hunting equipment—at the wholesale level, so you don’t see it when checking out at the sporting goods store. That money flows back to state fisheries and wildlife agencies as “restoration funds” to help improve the health of animal populations and their habitats.

And here’s a little trivia question that’ll stump most people, even wildlife professors. Why is the fishing excise tax 10%, but hunting is 11%? The answer is that the Pittman-Robertson program was created before World War II, and during the war all excise taxes (paid on lots of luxury items, like cigarettes and alcohol) were increased by 10%–so the hunting tax went to 11%. The Dingell-Johnson program was created after the war and set at the usual round number of 10%. Cool, eh?

So, should you ever confront the argument that fishing and hunting is bad for wildlife, take a step back and remember who started all this and who still pays for most of it—the guy in the bass boat and the gal in the orange vest!

References:

goHunt. How did hunting fees start? Available at: https://www.gohunt.com/read/how-did-hunting-fees-start#gs.4mtzs3. Accessed April 12, 2019

Lawrence, Brent. Hunters, anglers: The backbone of wildlife conservation. USFWS Pacific Region. Available at: http://usfwspacific.tumblr.com/post/119301140095/hunters-anglers-the-backbone-of-wildlife. Accessed April 12, 2019.

Palmer, T. S. 1904. Hunting Licenses: Their History, Objects and Limitations. US Department of Agriculture, Government Printing Office. Available at: https://archive.org/details/hunting00tspa/page/n3. Accessed April 120, 2019.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Hunters as Conservationists. Available at: https://www.fws.gov/refuges/hunting/hunters-as-conservationists/. Accessed April 12, 2019.