At the time it happened, the Johnstown Flood was the worst natural disaster in the history of the United States. It was the biggest news story since the assassination of President Lincoln, 24 years earlier. And it is a lesson of tragic proportion that dams, which do much good, are also tremendously dangerous.

The spring of 1889 had been a wet one in western Pennsylvania. Johnstown, a town of 30,000 residents a bit east of Pittsburgh, and the surrounding area had experienced unusually high amounts of rainfall. Rain had been falling for several days leading up to the disaster that occurred on May 31. The Conemaugh River, which flowed through Johnstown, ran swollen and angry.

Fourteen miles upstream from Johnstown, a reservoir sat on the South Fork of the Conemaugh River. The reservoir, called Lake Conemaugh, had been impounded by the South Fork Dam, an earthen dam built in 1853. The lake was built to provide water to feed the many canals that transported canal boats throughout Pennsylvania and New York (learn more about the Erie Canal here). The lake covered 425 acres and was 50 feet deep at the dam. Both the dam and the reservoir were the largest in the U.S. at the time. But as the canal system was replaced for transportation by railroads, the dam and lake became obsolete and fell into poor condition.

A group of wealthy residents of Pittsburgh, including Andrew Carnegie and Andrew Mellon, bought the lake and dam in 1879 as a private fishing and recreational resort for themselves and their families. They made repairs to keep the dam intact, but the work was shoddy, performed by unqualified laborers. They also modified the dam in two ways. First, they lowered the dam by two feet to allow a wider road across the top. Second, they fitted the spillway with screens to keep the fish they stocked into the lake from escaping.

These changes proved catastrophic. When the heavy rainfall raised the water far above usual levels, large amounts of debris washed from the shorelines to the dam, clogging the screened spillway. The water built higher and began to flow over the top of the lowered dam. Spillways exist at dams to prevent water from ever going over the top of a dam, because the downstream side will erode under the rush of water coming over the top.

Conditions continued to worsen throughout the day of May 31. By mid-afternoon, warnings were being issued that the dam was in peril, but the news was slow getting downstream to Johnstown. At 3:15 PM, the dam burst. Twenty million tons of water blew through the dam, forming a wall of water 40 feet high, raging downstream at 40 miles per hour.

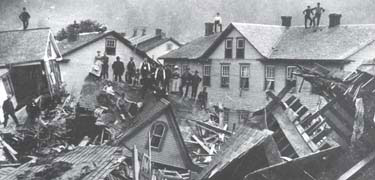

The wall hit Johnstown about 4 PM, with virtually no warning. The devastation was massive. Four square miles of downtown Johnstown were completely destroyed, including 1600 homes. At total of 2,209 people died; 99 entire families were wiped out. A railroad bridge through town became clogged with debris that grew to a 30-acre pile; it started on fire, killing 75 people who had sought refuge there from the raging waters.

The scale of the response matched the scale of the tragedy. The Red Cross, which had begun during the Civil War and was led by Clara Barton, came to Johnstown and stayed for months, building shelters and caring for the injured and homeless. This effort was the beginning of the ongoing work of the Red Cross when disasters strike across the world. Lawsuits were filed against the wealthy dam owners for negligence, but no judgments were ever made because of the difficulty of proving fault.

The story of the Johnstown Flood teaches several lessons. First, dams are essential features of modern infrastructure. The U.S. has more than 87,000 dams, and the worldwide total is many times that. Dams provide stable water supplies, prevent flooding, and generate power.

Second, however, is that dams are dangerous. If they are not built properly and maintained properly, they will fail. Hundreds of dam failures occur annually, although most are small and few take human life. The cause is almost always water flowing over the top of the dam, just as was the case in the Johnstown Flood (read about the world’s biggest dam disaster here).

And, third, although dams, particularly large dams, are not popular in the United States now (the golden era of dam building in the U.S. was from 1950 to 1980), they are very popular throughout the world. New dams continue to be built across most of the developing world, where the needs for water and power outweigh the environmental concerns that drive American decision-making.

References:

Degen, Paula and Carl. 2013. The Johnstown Flood of 1889. Eastern National, 64 pages.

History.com. The Johnstown Flood. Available at: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-johnstown-flood. Accessed May 7, 2019.

Johnstown Flood Museum. Statistics about the great disaster. Available at: https://www.jaha.org/attractions/johnstown-flood-museum/flood-history/facts-about-the-1889-flood/. Accessed May 7, 2019.

National Park Service. Johnstown Flood National Memorial. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/jofl/index.htm. Accessed May 7, 2019.