On June 29, 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the law that created Mesa Verde National Park. It was the sixth national park created, but the first established to “provide specifically for the preservation from injury or spoliation of the ruins and other works and relics of prehistoric or primitive man….”

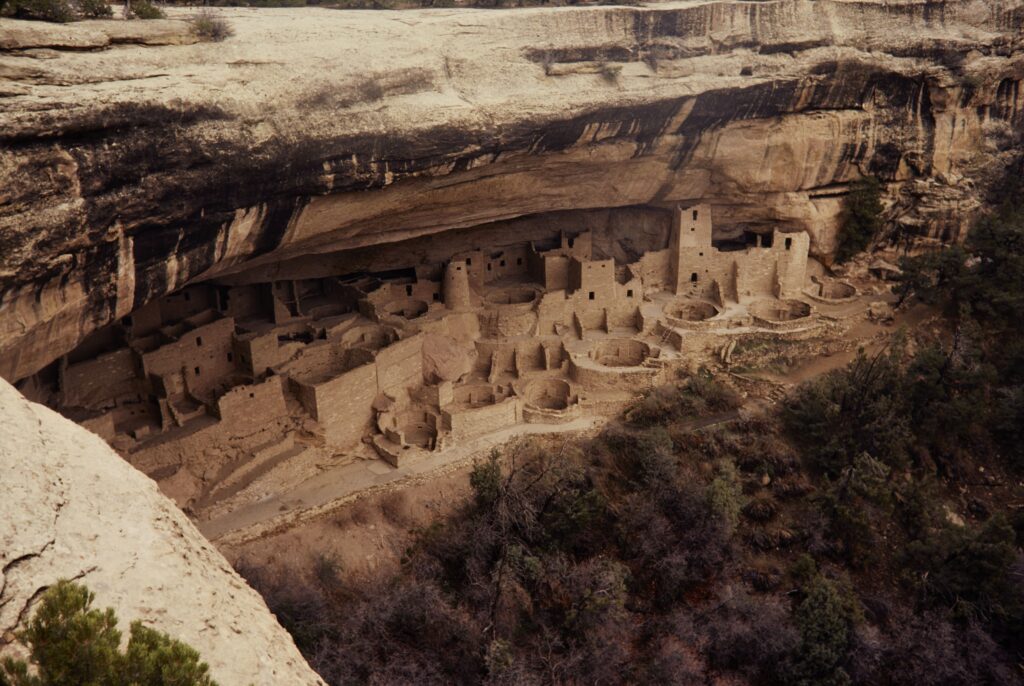

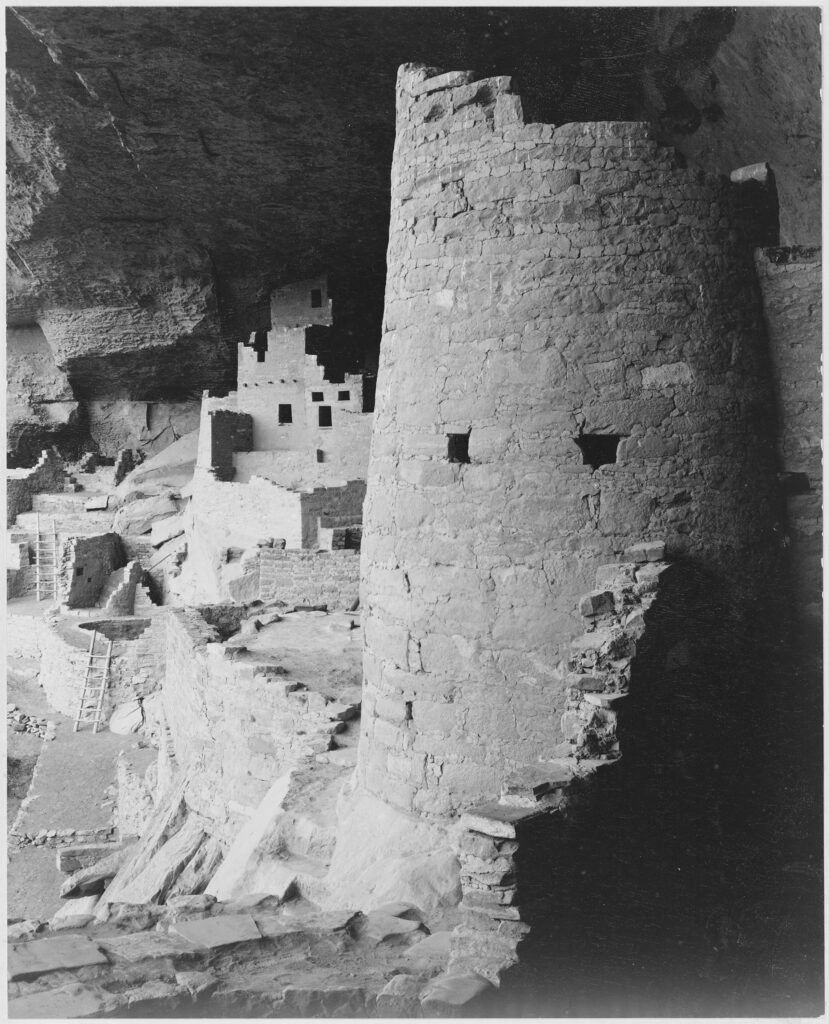

Mesa Verde was the right place to begin the mission of preserving the nation’s prehistory. The region had been occupied for nearly a millennium, until about 1300, by a civilization of pueblo-building Native Americans. First living on top of the mesa, the inhabitants later moved to the cliff-sides, building into shallow caves the massive adobe structures that we visit today. Archeologists have found more than 5,000 ancient sites, including relics of farms, irrigation systems and ceremonial areas as well as living structures. The global significance of Mesa Verde was recognized in 1978, when it became one of the eight original UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The park is relatively small as national parks go, covering just over 50,000 acres. Along with the ancient sites, the park includes 8,500 acres of federally designated wilderness. Mesa Verde itself is a high plateau, covered with pine forests that earn it the name of “green table.” Because of the large range in elevation between the top of the mesa and the canyons below it, the park contains four different vegetative ecosystems. It is prone to wildfires, and major blazes in the early 2000s burned about half of the park. Fortunately, because the major archeological sites are on cliff-sides, they have not been affected by recent fires.

But the real attractions are the pueblos. From 27 visitors who came in the park’s first year of 1906, annual visitation has risen to over 500,000. The first scientist to explore the park was Swedish archeologist Gustaf Nordenskjold, who wrote in his 1893 book, The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde:

“On account of their sheltered position not only the stone walls, but also in many cases the beams that support the floors between the different stories, are wonderfully well preserved. …we find still in a wonderful state of preservation the household articles and other implements once used by the inhabitants of the cliff-dwellings. Even wooden articles, textile fabrics, bone implements, and the like are often exceedingly well preserved, although they have probably lain in the earth for more than five centuries.”

Before the park was created, collectors removed most of those household articles, but, fortunately, the dwellings themselves still exist and many artifacts are now in museums. Many human and burial remains that had been removed have now been re-buried, in respect to the 24 Native American tribes that are associated with the site.

References:

National Park Service. Mesa Verde Administrative History. Available at: http://npshistory.com/publications/meve/adhi/contents.htm. Accessed June 28, 2017.

National Park Service. Mesa Verde National Park Timeline. Available at: http://www.visitmesaverde.com/media/399911/mesa-verde-national-park_timeline.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2017.

National Park Service. The 24 associated tribes of Mesa Verde. Available at: http://www.visitmesaverde.com/media/399909/mesa-verde-associated-tribes.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2017.

Nordenskjold, Gustaf. 1893. The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde. Mesa Verde Museum Association, translated from Swedish by D. Lloyd Morgan. P.A. Nordstedt & Sons, Chicago. Available at: https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Cliff_Dwellers_of_the_Mesa_Verde.html?id=dq9xAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed June 28, 2017.

UNESCO. Mesa Verde National Park. Available at: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/27. Accessed June 28, 2017.

US Federal Register. An Act Creating the Mesa Verde National Park. Chapter 3607, Fifty-Ninth Congress, 1906. Available at: https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/59th-congress/session-1/c59s1ch3607.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2017.