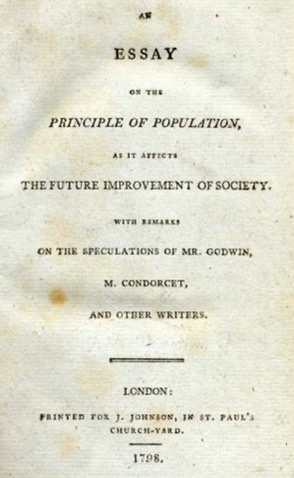

Thomas Robert Malthus, a British cleric turned economist, was born on February 13, 1766 (died 1834). Malthus is famous for a small booklet he published in 1798, entitled An Essay on the Principle of Population as it Affects the Future Improvement of Society, with Remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and Other Writers. Originally published anonymously, Malthus later took credit for the work and wrote a continuous string of expansions and updates throughout his life.

In the booklet, Malthus made the fundamental argument that the human species is destined for a recurring series of tragedies—war, famine, disease. The cause? Humans (and all species) reproduce so fast that they outstrip the production of resources—chiefly food—to support them. The consequence of too many people and not enough food is, therefore, tragedy. This concept—now called Malthusian or Neo-Malthusian—became the centerpiece of environmental thought in the 1960s as ecologists wrestled with worries over a rapidly growing world population.

Malthus grew up in the small market town of Dorking, in southern England. He was educated at home by his father, until enrolling at Cambridge University’s Jesus College. He was ordained into the Anglican Church. He became a professor of “political economy”—the first such post in England—and taught at a college in Hertfordshire, England, for his entire life. He wrote much about economic theory, most of which was contrary to conventional thought at the time. For example, while others were suggesting that human life would eventually evolve to a state of perfection, Malthus believed otherwise. Helping the poor, he thought, would just lead them to have more children, which would produce more poverty. The obvious endpoint would be famine, disease and strife, leading to a reduction in population through misery—and then the cycle could begin again.

He expressed these ideas in his 1798 booklet, and it found an immediate and sympathetic audience. However, we remember Malthus today because his message especially resonated when the science of ecology arrived in the 20th Century. Ecologists studying populations of animals watched as their numbers grew at exponential rates to high densities, outstripping their food supplies and then ending in massive starvation. They revived Malthus’ ideas to warn post-World-War-II society that the rapid growth of human populations would end up the same way. When Paul Ehrlich, the Stanford ecologist, wrote The Population Bomb in 1969, he again popularized Malthus’ view of the human condition.

Fortunately, neither Malthus’ dire view nor Ehrlich’s have come to pass. With the huge agricultural improvements that we know as the Green Revolution, food supply has grown faster than population (learn more about the green revolution here). And improvements in standard of living throughout the world have led not to higher population growth rates, but to lower ones.

References:

Encyclopedia Britannica. Thomas Malthus. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Malthus. Accessed February 12, 2017.

The Victorian Web. Thomas Robert Malthus. Available at: http://www.victorianweb.org/economics/malthus.html. Accessed February 12, 2017.

Understanding Evolution. The Ecology of Human Populations: Thomas Malthus. University of California, Berkeley, Understanding Evolution website. Available at: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/history_07. Accessed February 12, 2017