Yes, the official opening date of the Natural History Museum in London was April 18, 1881, when the iconic building it still occupies saw its first visitors. But the exhibits in the museum have a history that starts considerably before the official opening.

The famed British Museum opened in 1753 when the eclectic collections of Sir Hans Sloane were transferred to the British government upon his death. Sloane’s collection included a little more than 70,000 items, from architectural remnants to fossils to biological specimens. It was a broad and idiosyncratic compilation, but suited well to the appetites of curious aristocrats at the time.

But as time went on and the British Museum’s collections grew in scope and scientific value, space became tight and an organizing rationale was needed. In 1856, Richard Owen, a renowned paleontologist, signed on to curate the natural history portion of the museum. He quickly convinced the directors that a separate natural history building would relieve the space crunch and provide a proper status for exploring the natural world.

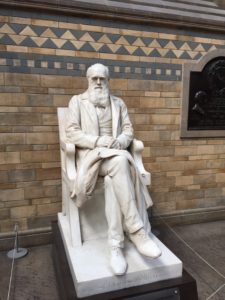

A few years later, architect Alfred Waterhouse took up the project, designing the building that became the Natural History Museum. When the new museum opened on April 18, 1881, it was an architectural and exhibition masterpiece. The sprawling building is covered in terra cotta tiles, used because they were resistant to the harsh air quality of Victorian London. The Romanesque structure dominates the landscape, with blocky spires at the corners and a soaring central tower. Waterhouse designed “a cathedral for nature,” as revealed by the interior. The central hall rises to a dizzying height, with walls of windows at the ends that resemble those of a church nave. Arched galleries like chapels line the side walls, topped by a higher floor of more intricate three-arched openings. At the end of the building, where an altar or statue of Jesus would adorn a cathedral, a broad staircase rises to an out-sized alabaster statue of Charles Darwin.

But then come the natural history details. The columns that border doorways to adjacent hallways are sculpted to resemble the main stems of both living and fossil plants. The columns are inhabited with climbing monkeys, perching birds, crouching frogs and trailing flowers. The ceiling is covered with tiles showing 162 plants representing the world’s flora—many of which were imported to England through the great voyages of exploration of that time.

The museum remained part of the British Museum until 1963, when it was separately chartered. The current name—the Natural History Museum, without a “British” or “London” modifier—arrived in 1992. From those early specimens has grown one of the largest natural history museums in the world. Today the museum houses 80 million specimens, representing the flora and fauna, both living and prehistoric, of the entire globe, along with mineral and other geological specimens.

Most museums in Victorian times were expensive to visit, but Owen insisted that the Natural History Museum be free and open to all. It remains so to this day, along with its parent, the British Museum. Consequently, it is the third most visited attraction in London, hosting more than 4.6 million enthralled visitors in the past year (the record was 5.6 million in 2013-2014).

They go to see astounding displays. For four decades, the central hall held a Diplodocus skeleton that visitors fondly named “Dippy.” It has been replaced by a hanging blue whale skeleton to represent the living biodiversity of the earth. A wildlife garden adjoins the west side of the museum, a quiet refuge from the crowds. The newest addition is the Darwin Centre, which holds glass-walled laboratories for the museum’s 200 scientists where visitors can watch and participate in scientific work. The dinosaur displays are considered the finest in the world. My favorite area, however, is the “Treasures of the Museum” exhibit that shows a series of remarkable objects—an original copy of The Origin of Species, a collection of butterflies made by Alfred Russel Wallace, and many other priceless specimens.

References:

Pavid, Katie. 2018. Indexing Earth’s wonders: a history of the Museum. Natural History Museum, 17 April 2018. Available at: http://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/indexing-earths-wonders.html. Accessed April 17, 2018.

Natural History Museum. History and architecture. Available at: http://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/history-and-architecture.html. Accessed April 17, 2018.