Tero Mustonen, Finnish Environmentalist, Born (1976)

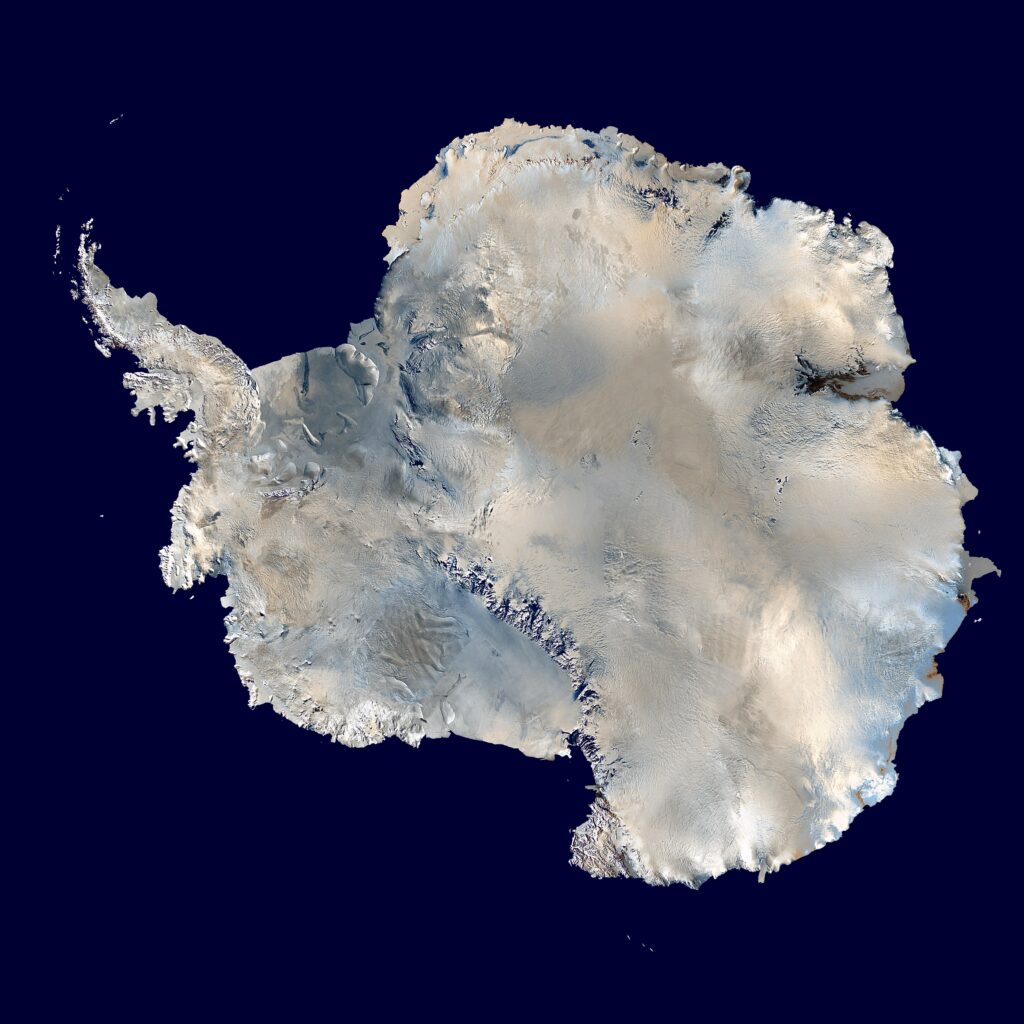

Save the rainforest! That’s what we hear over and over—and for good cause. But at the other ends of the earth, there are also valuable ecosystems, doing valuable work to sustain our lives. Tero Mustonen is a champion for Arctic ecosystems, urging us to protect them from misuse, and doing his utmost to make that happen.

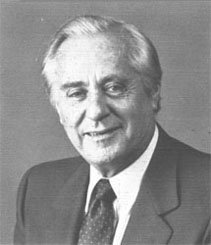

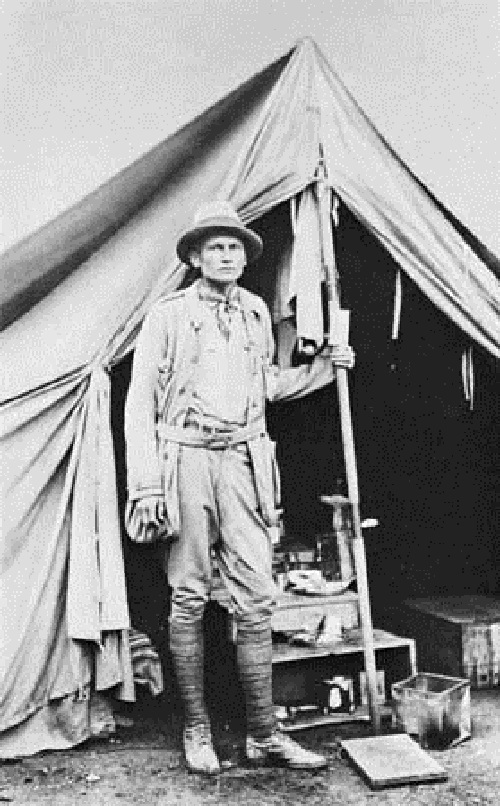

Tero Mustonen was born (June 23, 1976) and raised in the small Finnish village of Selkie in far eastern Finland, only 35 miles from the Russian border. “I grew up in a fishing family. We were close to nature, living without running water in a small village in the boreal forest each summer.” He still lives in Selkie, where he continues to fish commercially and has become the head of the village. He believes that indigenous knowledge is essential to keeping Arctic ecosystems—all ecosystems, really—functioning properly. “In most places around the world, we do not know how things were prior to the 1900s, so indigenous memory can inform about changes and ecosystems….Without indigenous peoples and their wisdom, there would not be nearly enough preserved biodiversity.”

But Mustonen also understands that modern science and techniques are necessary tools to sustain nature. “I decided I needed scientific training to understand properly what was going on in the landscapes I knew. I often say that I first went to a real school, fishing on the ice, and then I learned the analytical tools to make the link to scientific knowledge.” He learned well, earning his doctorate in 2009 from the University of Eastern Finland.

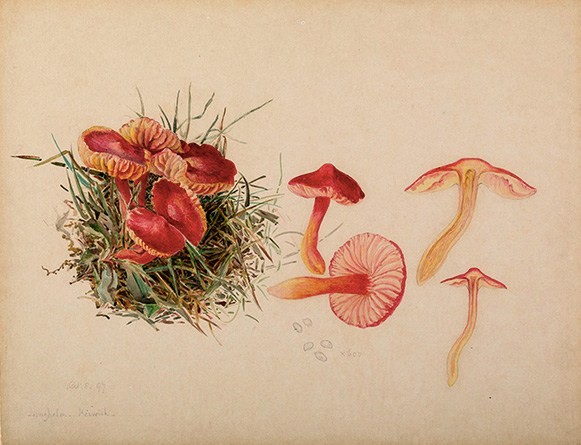

That scientific knowledge helped Mustonen put his experience into a broader context—a context built on peat. About 30% of Finland is covered in peat, a compressed material of soil and decomposing vegetation. The peat does not decompose completely due to insufficient oxygen, thereby absorbing and storing huge quantities of CO2. Peat has been used locally throughout time as a fuel source. But the local practices were sustainable, and the vast peatlands of Finland were hardly changed until the end of World War II. Then, the country drained nearly half of its peatlands for mining. Mustonen recently noted, “Intact peatlands were seen as unproductive wastelands….we have lost approaching half of our wet peatlands and their wildlife—more than 12 million acres.”

Mustonen has developed a comprehensive strategy for combating these losses and restoring the peatlands—rewilding, he calls it. In 2000, he created the Snowchange Cooperative “…to integrate Indigenous knowledge with science and to advance the voices of traditional communities in the North, while helping them maintain fisheries and reindeer herding in the face of climate change and other threats.”

And it works. He and his colleagues at Snowchange talk with Indigenous people and village elders to learn the history of the local peatlands. They use that knowledge to employ modern techniques to make initial restoration changes. “I’m not a big fan of machinery, but we need excavators at first to block ditches, raise [water] tables and restore water flow.” Then they let nature take over, accepting that the results will occur gradually and that the peatlands are unlikely to return to their former state. “We do rewilding rather than strict ecosystem restoration…. But we can recover rich, biodiverse wetlands.” The restored sites attract native wildlifeand once again begin to remove CO2 from the air. “One moonscape we took over in 2015 has gone from three bird species to 210, including rare waders such as Terek sandpipers.”

They started small, working in Mustonen’s home village of Selkie in 2010. When a mining company began working around the village, acid mine drainage began killing fish. But the company agreed to let Snowchange restore three wetlands. From there, the group began buying abandoned industrial sites and “rewilding” them. Today, Snowchange has about 80 sites under rewilding, covering 130,000 acres.

Mustonen has expanded his efforts across the Arctic and also into the Pacific, particularly with the Maori of New Zealand (unfortunately, their work in Russia ended when Russia invaded the Ukraine). That process seeks to restore not only ecosystems, but also Indigenous peoples. “We never wanted to be just a conservation organization. We are appalled that the Sami people in northern Finland … are the only Indigenous peoples in Europe who don’t have proper land rights.”

In the U.S., Mustonen’s approach is called community-based conservation. Making local people, including Indigenous peoples, part of the decision-making and implementation processes grows friends rather than enemies and develops partners rather than resisters. For his approach, Mustonen won one of the six 2023 Goldman Environments Prizes, often called the “Green Nobels.” And I noble approach it is!

References:

Goldman Environmental Prize. 2023. Tero Mustonen. Available at: https://www.goldmanprize.org/recipient/tero-mustonen/#recipient-bio. Accessed January 20, 2024.

Pearce, Fred. 2023. Finland Drained Its Peatlands. He’s Helping Bring Them Back. Yale Environment 360. Available at: https://e360.yale.edu/features/tero-mustonen-interview. Accessed January 20, 2024.

Schueman, Lindsey Jean. 2023. Climate Hero: Tero Mustonen. One Earth, April 25, 2023. Available at: https://www.oneearth.org/conservation-hero-tero-mustonen/. Accessed January 20, 2024.

Snowchange Cooperative. 2024. Home. Available at: http://www.snowchange.org/. Accessed January 20, 2024.

University of Eastern Finland. 2023. Tero Mustonen wins the Goldman Environmental Prize, a.k.a. the “Green Nobel.” 24.4.2023. Available at: https://www.uef.fi/en/article/tero-mustonen-wins-the-goldman-environmental-prize-aka-the-green-nobel. Accessed January 20, 2024.