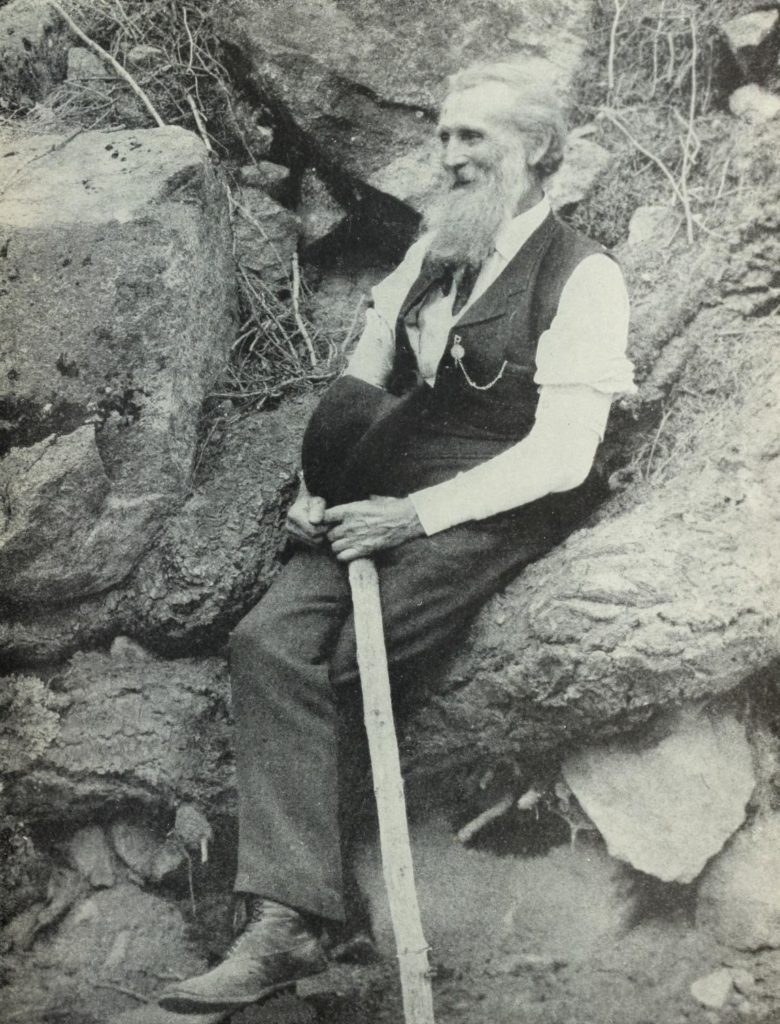

John Muir, the father of American conservation, loved the Yosemite Valley like no other place on earth. He wrote, “How vividly my own first journey to Yosemite comes to mind. It was bloom-time of the year over all the lowlands and ranges of the coast; the landscape was fairly drenched with sunshine, the larks were singing, and the hills so covered with flowers that they seemed to be painted….” Those of us lucky enough to have visited Yosemite feel much like Muir. And we owe the existence of Yosemite National Park largely to John Muir’s efforts.

Yosemite was well known to California tourists by the time Muir arrived in 1868. In fact, part of the area was already a park. The lands belonged to the federal government, and in 1864, President Lincoln had signed a law that transferred Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the state of California for a park. This law required that “the premises shall be held for public use, report, and recreation; shall be inalienable for all time.” Although Yellowstone is officially the nation’s first “national park” (created in 1872), many people consider this action to be the inspirational spark for the national park idea.

The park was created, but California did little to manage its use. Quickly the Yosemite Valley became overrun with shabby hotels and other buildings, sheep grazing denuded the meadows, and timber harvest carried away the forest.

John Muir was not about to accept this travesty. Muir formed a partnership with magazine publisher Robert Underwood Johnson with the goal of preserving the larger ecosystem surrounding the valley. Protecting the whole was important, Muir argued, because “the branching canons and valleys of the basins of the streams that pour into Yosemite are as closely related to it as are the fingers to the palm of the hand—as the branches, foliage and flowers of a tree to the trunk.” Muir wrote articles for Johnson’s magazine; Johnson lobbied his influential friends for political support. They were almost immediately successful. On October 1, 1890, President Benjamin Harrison signed the law that created Yosemite National Park

There was still a problem, however. California still controlled the Yosemite Valley, a geographic hole in the doughnut of the national park. And that hole was an ecological disaster. Mounting the same sort of campaign that he had done before, Muir was once again successful. In 1906, Yosemite Valley was returned to federal ownership by California and became part of Yosemite National Park. Today, the park stands as a unified ecosystem covering about 1200 square miles and is surrounded by national forests and other protected lands that help keep the magnificence of Yosemite intact.

And people still love it. Record visitation occurred in 2016, the National Park Service’s centennial year, when just over 5 million people went to Yosemite. Yosemite ranks sixth in visitation among all national parks.

Yosemite does have one sad chapter. After an earthquake and fire destroyed most of San Francisco in 1906, the city proposed that a valley within Yosemite be dammed to make a reservoir to create a large and reliable water source. John Muir again came to the park’s defense: “Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.” Eventually Muir lost his argument, and the Hetch Hetchy Valley was dammed and flooded—and remains so to this day.

References:

Gisel, Bonnie. A Short History of Yosemite National Park. Sierra Club. Available at: https://content.sierraclub.org/grassrootsnetwork/sites/content.sierraclub.org.activistnetwork/files/teams/documents/A%20Brief%20History%20of%20Yosemite%20National%20Park%20by%20Bonnie%20Gisel.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2019.

National Park Service. Yosemite. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/yose/index.htm. Accessed July 18, 2019.

Nielsen, Larry A. 2017. Nature’s Allies—Eight Conservationists Who Changed Our World. Island Press, 255 pages.

OhRanger.com History of Yosemite. Available at: http://www.ohranger.com/yosemite/history-yosemite. Accessed July 18, 2019.