Whoever the Secretary-General of the United Nations might be, he (or she, maybe, someday) is unquestionably a world leader. But Ban Ki-moon, the UN Secretary-General from 2007 to 2016, deserves our special recognition as an environmental leader who moved climate change to the top of the world’s agenda.

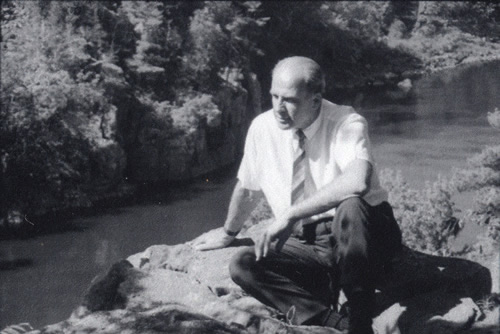

Ban Ki-moon was born on June 13, 1944, in South Korea when it was still occupied by Japan. As a boy, he lived through the Korean War. He said, “I grew up in war and saw the United Nations help my country to recover and rebuild. That experience was a big part of what led me to pursue a career in public service.” He graduated from Seoul National University and then received an M.A. from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard.

Ban immediately entered his nation’s diplomatic service. Among his many positions, he was the South Korean Ambassador to Austria (1998-2000) and Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2004-2006). On January 1, 2007, he was elected as Secretary-General of the United Nations; he was unanimously re-elected for a second five-year term that ended on December 31, 2016.

While Secretary-General, Ban focused on climate change as one of his highest priorities. He led the 2007 Climate Change Summit in Bali, the Rio+20 Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro, and the 2015 Paris meeting that led to the Paris Climate Agreement. He oversaw the worldwide focus for sustainable development through the Millennium Development Goals and led the formation of the subsequent Sustainable Development Goals that began in 2015 (learn more about the Millennium and Sustainable Development Goals here).

Since leaving the UN at the end of 2016, Ban has continued his work on climate change and sustainable development. With Dr. Heinz Fischer, former president of Austria, he founded the Ban Ki-moon Centre for Global Citizens, a non-profit organization that seeks to “use its independence, expertise and network to work for peace, poverty eradication, empowerment of youth and women, justice and human rights worldwide.” He is President and Chair of the Council of the Global Green Growth Institute, which works through 36 member nations to support and promote “strong, inclusive and sustainable economic growth in developing countries and emerging economies.”

I will let Mr. Ban’s views on climate change and sustainability speak for themselves.

“Saving our planet, lifting people out of poverty, advancing economic growth … these are one and the same fight. We must connect the dots between climate change, water scarcity, energy shortages, global health, food security and women’s empowerment. Solutions to one problem must be solutions for all.”

“Climate change has happened because of human behavior, therefore it’s only natural it should be us, human beings, to address this issue.”

“It is unfair, politically wrong, morally wrong when countries that have not contributed much to the climate phenomena should bear the cost and consequences. If industrialised countries who have contributed seriously negatively to this climate phenomena are not taking their own responsibility than who can?”

“We have reached 2020 but because of the lack of political will we have not yet been able to mobilise that which is absolutely, urgently necessary for developing countries to mitigate and adapt.”

“We must turn the greatest collective challenge facing humankind today—climate change—into the greatest opportunity for common progress towards a sustainable future.”

References:

AZ Quotes. Ban Ki-moon Quotes About Climate Change. Available at: https://www.azquotes.com/author/21299-Ban_Ki_moon/tag/climate-change. Accessed February 25, 2020.

Ban Ki-moon Centre for Global Citizens. Mission. Available at: https://bankimooncentre.org/mission. Accessed February 25, 2020.

Encyclopedia Britannica. Ban Ki-Moon. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ban-Ki-moon. Accessed February 25, 2020.

Global Green Growth Institute. About GGGI. Available at: https://gggi.org/about/. Accessed February 25, 2020.

United Nations. Former Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. Available at: https://www.un.org/sg/en/formersg/ban.shtml, Accessed February 25, 2020.

Zacharias, Anna. 2020. Industrialised countries must help solve climate change, says Ban Ki-moon. The National UAE, January 8, 2020. Available at: https://bankimooncentre.org/mission. Accessed February 25, 2020.