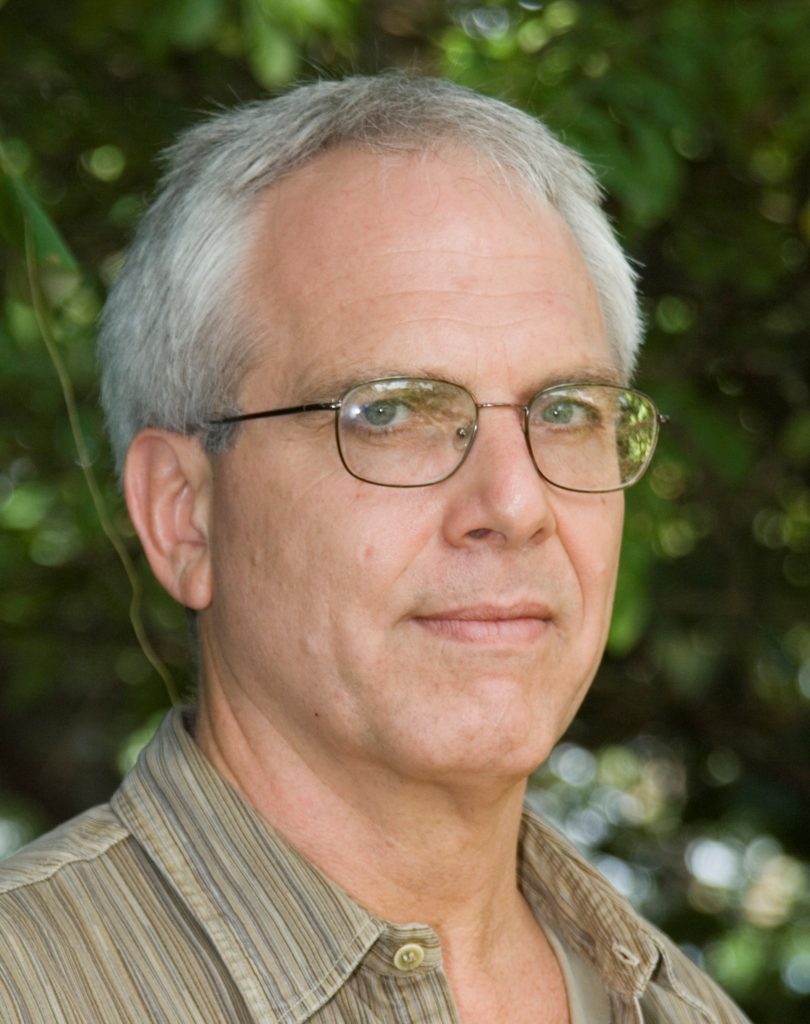

Explorers generally look to the far horizon for their adventures, but with the right perspective, nature provides adventures just as thrilling right in one’s own backyard. Look there, and you might find yourself with the reputation as “the greatest living naturalist in America.” Such was the case for Edwin Way Teale, born on June 2, 1899.

Teale was born in Joliet, Illinois, just south of Chicago. His original middle name was Alfred, but he changed it to Way when he was 12, purportedly because he thought Alfred was not sufficiently grand for someone who would become a famous naturalist (Way was also his mother’s maiden name). He spent summers at his grandparents’ farm, Lone Oak, in the sand-dune region of northern Indiana, on the shores of Lake Michigan. Of his summers, Teale said that the farm was “a starting point and a symbol. It was a symbol of all the veiled and fascinating secrets of the out-of-doors. It was the starting point of my absorption into the world of Nature.”

He studied English at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, where he met his future wife and lifelong collaborator, Nellie Donovan. The couple moved to New York, where Teale took a Master’s degree at Columbia and then a job as a writer for the magazine Popular Science. He toiled at the magazine for a decade before resigning on his “own personal independence day.”

And so began a career in which Teale embedded himself in nature and wrote about it with scientific clarity and compelling emotion. He also became an expert nature photographer, pioneering up-close images of insects. Unlike other nature writers and photographers, who concentrated on nature’s grandeur, Teale instead found beauty and wonder in the intrigue of his immediate surroundings. He wrote 32 books, mostly about nature, from his boyhood memoir, Dune Boy, to a four-book series on nature, season by season. One of the season books, Wandering Through Winter, earned Teale the Pulitzer Prize for Non-fiction in 1966. He and Nellie chased nature across the country in their Buick sedan, travelling more than 75,000 miles in pursuit of the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Although Teale was not a scientist, his writings brought him into “the vanguard of the new aristocracy of naturalists, according to famed ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson (learn more about Peterson here). He was friends with Rachel Carson, and some suggest it was Teale’s urging that convinced Carson to write her second book, The Sea Around Us (after the commercial failure of her first book) (learn more about Carson here). He won numerous prizes and awards from conservation, scientific and literary organizations.

But Edwin Way Teale was a nature writer, and the best way to get to know him is through his own words.

“To the lost man, to the pioneer penetrating a new country, to the naturalist who wishes to see the wild land at its wildest, the advice is always the same—follow a river. The river is the original forest highway. It is nature’s own Wilderness Road.”

“For observing nature, the best pace is a snail’s pace.”

“Looking at life through the eyes of a Daddy long legs: Imagine walking on legs so long you could cover a mile in fifty strides! Imagine looking to either side through eyes set not in your head but in a … hump in the back! Imagine your knees, when you walked, working a dozen feet or more above your head.”

“A man who never sees a bluebird only half lives.”

“If I were to choose the sights, the sounds, the fragrances I most would want to see and hear and smell—among all the delights of the open world—on a final day on earth, I think I would choose these: the clear, ethereal song of a white-throated sparrow singing at dawn; the smell of pine trees in the heat of the noon; the lonely calling of Canada geese; the sight of a dragon-fly glinting in the sunshine; the voice of a hermit thrush far in a darkening woods at evening; and—most spiritual and moving of sights—the white cathedral of a cumulus cloud floating serenely in the blue of the sky.”

References:

Archive.today. Edwin Way Teale Papers 1981.0009. Available at: https://archive.ph/20140828224410/http://137.99.31.136:8080/xtf/view?docId=finding_aids/MSS19810009.xml&doc.view=print;chunk.id=.

Holland, Robert. 1984. Edwin Way Teale. Letter to Editor, The New York Times, August 12, 1984. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1984/08/12/books/l-edwin-way-teale-138720.html.

Indiana Historical Bureau. Edwin Way Teale. Available at: https://www.in.gov/history/markers/EdwinWTeale.htm.