There are only a few conservationists who have achieved lasting international fame. But there are many who have done remarkable things at a somewhat smaller geographic scale. Today I write about such a person, who concentrated her career on one particular type of ecosystem—and made the earth a lot more sustainable.

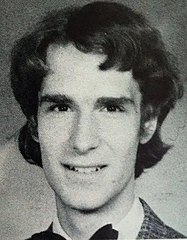

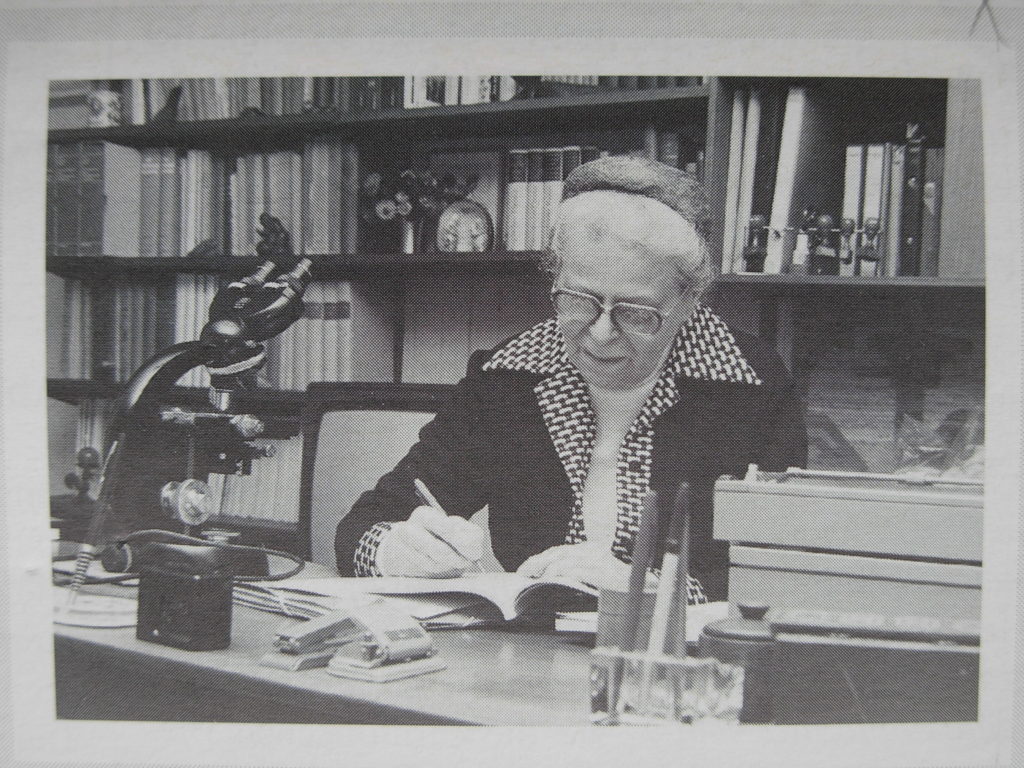

Elsie Quarterman was born in Valdosta, Georgia, on November 28, 1910 (died 2014, at 103 years old!). She grew up on a family farm, where walks with her mother and aunts nurtured her interest in plants. She graduated from what is now Valdosta State University in 1932 and then received an MS from Duke University in 1943. She taught at Vanderbilt University in Nashville from then on. But knowing that she would need a doctorate to keep her job, she simultaneously pursued her Ph.D. in botany at Duke, which she received in 1949.

Her doctoral research focused on the ecology of “cedar glades,” a unique Tennessee habitat. Cedar glades are underlain by limestone rock with shallow soils—no deeper than about 8 inches—that support correspondingly unique plant communities. Red cedar trees often border these areas, where gaps in the rocky substrate accumulate deeper soils that allow scrubby tree cover. But within the cedar glades themselves, the vegetation is largely grasses and flowering plants. Quarterman’s research established the composition of the plant communities and related their structure to soil conditions, exposure and inter-species competition. Although once covering 5% of the region, human modification of the landscape has eliminated most of them.

In the early 1960s, Quarterman and a colleague saw an unusual flower growing in a cedar glade as they drove by. It turned out to be the Tennessee coneflower, Echinacea tennesseensis, a species that had been declared extinct decades earlier (also called the Tennessee purple coneflower). She found other isolated populations in other cedar glades and studied the plant’s distribution and life history. Because of her work, the Tennessee coneflower was one of the first plants placed on the U.S. endangered species list—and more importantly because of her efforts to establish new populations in suitable habitats, the species recovered and was delisted in 2011.

Along with becoming the world’s authority on cedar glades, Quarterman made equally important contributions to Vanderbilt University. She was one of the nation’s first female botany professor to earn a doctorate, and in 1964 she became the first woman to chair an academic department at Vanderbilt. She taught a dozen doctoral students, who have carried on her work on cedar glades along with their own students. After retiring in 1976, she continued working and exploring actively through her 90’s, always ready for a hike to look at plants, especially if students could join her.

The list of her professional achievements is staggering. She was a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and held important positions in many other botanical and conservation organizations. She founded the Tennessee Protection Planning Committee, and was a founding member of the Tennessee chapter of The Nature Conservancy. She received a long list of awards for her role as one of the region’s leading plant community ecologists. A particular cedar glade, which was among her major research sites, was named in her honor in 1988; the Elsie Quarterman Cedar Glade State Natural Area covers 185 acres in Rutherford County, Tennessee, and contains a recovery population of Tennessee coneflowers.

Dr. Elsie Quarterman won’t make the list of the most important people of the century and she doesn’t have a biography in Encyclopedia Britannica or anywhere else, but she should have. I find her work more inspiring for the very reason that most people don’t know about her. She focused on the importance of one habitat and its unique diversity, making sure that we saved some for the future. Because of hundreds of dedicated people like her, our world is that much better than it would have been without them. Thank you, Dr. Quarterman.

References:

Canopy Roads of South Georgia. Dr. Elsie Quarterman, November 28th 1910 – June 9th 2014. Available at: http://www.okraparadisefarms.com/blog/2014/06/dr-elsie-quarterman-november-28th-1910-june-9th-2014.html. Accessed November 27, 2019.

Furlong, Kara. 2014. Elsie Quarterman, who rediscovered Tennessee coneflower, dies at 103. Vanderbilt University News, June 12, 2014. Available at: https://news.vanderbilt.edu/2014/06/12/elsie-quarterman/. Accessed November 27, 2019.

Hemmerly, Thomas E. Cedar Glades. Tennessee Encyclopedia. Available at: https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/cedar-glades/. November 27, 2019.

Quarterman, John S. et al. 2014. Elsie Quarterman (1910-2014), Centenarian Ecologist. Clan Sinclair. Available at: http://sinclair.quarterman.org/who/elsie_ecologist.html. Accessed November 27, 2019.

Tennessee Department of Environment & Conservation. Elsie Quarterman Cedar Glade Class II Natural-Scientific State Natural Area. Available at: https://www.tn.gov/environment/program-areas/na-natural-areas/natural-areas-middle-region/middle-region/elsie-quarterman-cedar-glade.html. Accessed November 27, 2019.