A few years ago, PBS and film-maker Ken Burns combined to produce the documentary series, “The National Parks—America’s Best Idea.” Many of us would agree—the 400+ units of the National Park Service are a treasure beyond accounting. And why have those treasures been preserved and prospered over a century dominated by growing population and development? Because an “Organic Act” established the National Park Service on August 25, 1916.

Of course, the national park idea itself preceded the National Park Service (NPS) by about half a century. President Lincoln established the first national park, Yosemite, in 1864, but gave management of it to the state of California. Eight years later, in 1872, President Grant established the first official national park—Yellowstone. A few other parks were created in the following decades. Preserving public lands took a big leap forward in 1906, when President Teddy Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act, which gave presidents the power to declare federal land protected as national monuments.

Of course, the national park idea itself preceded the National Park Service (NPS) by about half a century. President Lincoln established the first national park, Yosemite, in 1864, but gave management of it to the state of California. Eight years later, in 1872, President Grant established the first official national park—Yellowstone. A few other parks were created in the following decades. Preserving public lands took a big leap forward in 1906, when President Teddy Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act, which gave presidents the power to declare federal land protected as national monuments.

But this was a haphazard process. Some protected lands were under the Secretary of Interior, others under the Secretary of Agriculture, and still others under the Secretary of War. And protection itself was always in doubt, as proven in 1913, when two dams were authorized inside Yosemite National Park to provide water and power for San Francisco. A better system was needed if our great national treasures were to survive.

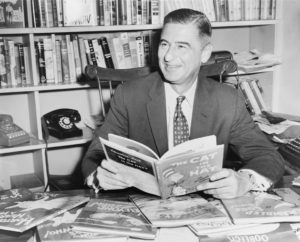

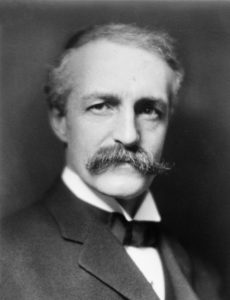

Stephen Mather had a plan. Mather was a California businessman who made “20-mule-team Borax” a highly popular cleaning product; and that product made Mather a very rich man. But he also suffered from what we now call bipolar disease, and being outdoors in nature helped him escape the bouts of depression that plagued him. He appreciated nature for himself, but he also understood that nature was part of America’s innate personality. Visiting Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks in 1914, he despaired over their poor management and care. He lobbied his friend, Secretary of Interior Franklin Lane, to do something. Lane did—he offered Mather the job as his Assistant Secretary in charge of parks.

Mather, along with colleague Horace Albright, took on the challenge. They improved the situation as best they could, hiring staff (which Mather paid with his own funds), expanding parks (with land purchased by Mather himself), professionalizing the training and procedures at parks and encouraging visitation. But they understood that the great mission of their agency needed higher status if it were to prosper. Along with other dedicated conservationists, Mather and Albright lobbied congress for two years, achieving their goal of a National Park Service Organic Act when President Wilson signed the agency into existence on August 25, 2016.

An “organic act” is important because it establishes a federal land-management agency through passage of a law approved by both houses of Congress and signed by the President. Therefore, the agency cannot be changed administratively—reorganized, eliminated, combined, broken apart, given a new mission—like other parts of the executive branch. An organic act gives an agency permanency, exactly what is needed for the part of our government devoted to preserving our national treasures for all time.

The NPS Organic Act established the National Park Service, and gave it several specific features. First, it gave the NPS jurisdiction of all “national parks, monuments and reservations,” moving lands from other agencies to the NPS. From 35 units in 1916, the NPS continued to grow, with transfers of lands from other agencies and the addition of newly created parks and other areas through time. Today, the NPS system includes 417 separate “units” covering 84 million acres. Some are huge, like Yellowstone, others are small, just a historic building and its surrounding lands.

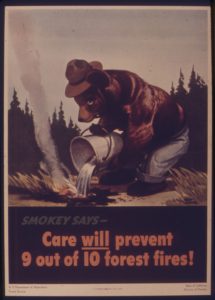

Second, the organic act defined the purpose of the NPS. That purpose is “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” The act answered the question of whether resources could be exploited in national parks—and the answer is “no.”

Third, the organic act gave the NPS authority to use whatever tools and techniques it required to accomplish its mission. Rules and regulations can be set to avoid damage and control use. Resources can be managed—timber cut, animals harvested, facilities built—to protect the ecosystems and allow their use. NPS units are not wildernesses (although parts of some are), but meant to be accessible to and enjoyed by visitors. And visit them we do. In 2017, the NPS reported total recreational visitors of 330,882,751—more than one visit on average by every person in the United States.

Stephen Mather became the first Director of the National Park Service, a job he held from 1916 to 1929, just before his death. Plaques erected in his honor in all parks at the time read, “There will never come an end to the good that he has done.” Americans disagree about many things today, but I suspect that we would be nearly unanimous that there is no end to the good that our national parks have done—and will do.

References:

Dilsaver, Lary M. 1994. America’s National Park System—The Critical Documents. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anps/index.htm. Accessed July 3, 2018.

National Park Service. Quick History of the National Park Service. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/articles/quick-nps-history.htm. Accessed July 3, 2018.

PBS. Stephen Mather (1867-1930). The National Parks, America’s Best Idea. Available at: http://www.pbs.org/nationalparks/people/nps/mather/. Accessed July 3, 2018.