When I was a middle-schooler (or the equivalent, since Chicago didn’t have middle schools in 1960), I waited eagerly for every issue of National Geographic. That magazine took me to faraway places filled with exotic plants, animals, people and landscapes—and taught me to want to protect and conserve them.

Educated and cultured homes in those days had two things that defined them, a set of encyclopedias and a subscription to National Geographic. In my case, however, the magazine came several months after it reached subscribing homes. My mother, who cleaned a doctor’s office, would bring home an issue every month that was about six months old, having rotated the magazines in the office. Never mind not bringing me “breaking news,” it brought me a big, beautiful world.

We owe thanks to the far-sighted folks who organized a new group in mid-January, 1888. Thirty-three intellectual leaders met in Washington, DC, to hash out the plans for “a society for the increase and diffusion of geographical knowledge.” A week later, they returned for more discussion, now with twice as many people attending. The next week, on January 27, the organization was incorporated as the National Geographic Society.

The first issue of National Geographic appeared in October, 1888, sent to the society’s 200 charter members. It was a scholarly journal, with no pictures. By the next year, the magazine began including colored drawings and the fold-out maps that have become regular features. The society sponsored its first expeditions, to Alaska and Canada, during 1890-1891.

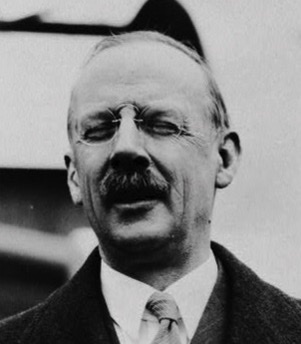

But it was Alexander Graham Bell who steered the magazine toward a more popular future. Elected president of the society in 1898, he demanded the magazine include “pictures, and plenty of them….THE WORLD AND ALL THAT IS IN IT is our theme, and if we can’t find anything to interest ordinary people in that subject, we better shut up shop….” Soon after, the new editor, Gilbert H. Grosvenor, included eleven pages of photographs of Tibet. He expected to be fired, but was instead congratulated by members. The change wasn’t universally embraced—later some board members resigned because the magazine was becoming a “picture book.”

But the vision of Bell and Grosvenor won the day, and ordinary people flocked to the magazine (Grosvenor became the organization’s president in 1920 and served in that role until 1954). Membership (that is, magazine subscriptions) passed one million in 1926. Revenue from memberships allowed the society to fund explorers investigating the farthest reaches of the globe, more than 100 through the 1950s (and hundreds more since), and the magazine became the “publication of record for their discoveries.”

The list of world-leading scientists and explorers funded or publicized by National Geographic seems unending. Jacques Cousteau published articles about the under-sea world (learn more about Cousteau here). Louis and Mary Leakey reported their discovery of humanoid fossils at Olduvai Gorge. The society sponsored the initial work of Jane Goodall to study chimpanzees in Tanzania (learn more about Goodall here). John Glenn carried a National Geographic Society flag into space. Dian Fossey was funded to study gorillas in Rwanda (learn more about Fossey here). The discovery of the Titanic wreck was announced through the National Geographic Society. Paul Sereno announced the world’s oldest dinosaur fossils. Sylvia Earle conducted a five-year study of possible marine preserves.

National Geographic magazine and its clones have enormous outreach. The signature magazine is published in 34 languages and reaches 60 million people monthly. The National Geographic Channel is broadcast in 38 languages in 171 countries to 440 million households. Add to that the society’s digital presence, internet applications, social media, websites and newsletters, and it is hard to avoid the society’s influence on education, science and conservation.

But for me, National Geographic will always be the dog-eared magazines with a bright yellow border that landed on our kitchen table each month, six months out of date. They were the source of most of my school reports and the inspiration for a career in conservation.

References:

Gale Cengage Learning. The History of the National Geographic Society. Available at: http://gale.cengage.co.uk/national-geographic-virtual-library/history.aspx. Accessed January 31, 2018.

National Geographic Press Room. National Geographic Milestones. Available at: http://press.nationalgeographic.com/milestones/. Accessed January 31, 2018.

National Geographic Press room. National Geographic shows 30.9 Million Worldwide Audience via Consolidated Media report. Available at: http://press.nationalgeographic.com/2012/09/24/national-geographic-shows-30-9-million-worldwide-audience-via-consolidated-media-report/. Accessed January 31, 2018.