When science and politics mix, the result is usually bad—and science is generally the loser, but only in the short term. Such was the case of Nikolai Vavilov, an extraordinary Russian geneticist who ran afoul of Soviet doctrine under Jospeh Stalin.

Vavilov was born on November 25, 1887, to a wealthy family in Moscow (the “wealthy” part is foreboding). Always interested in natural sciences, he studied agronomy at the Moscow Agricultural Institute. There he formed his life’s goal—to use the new science of genetics to breed agricultural crops tailored to specific growing conditions (temperature, soil type, water availability), and, therefore, to rid the world of hunger and famine.

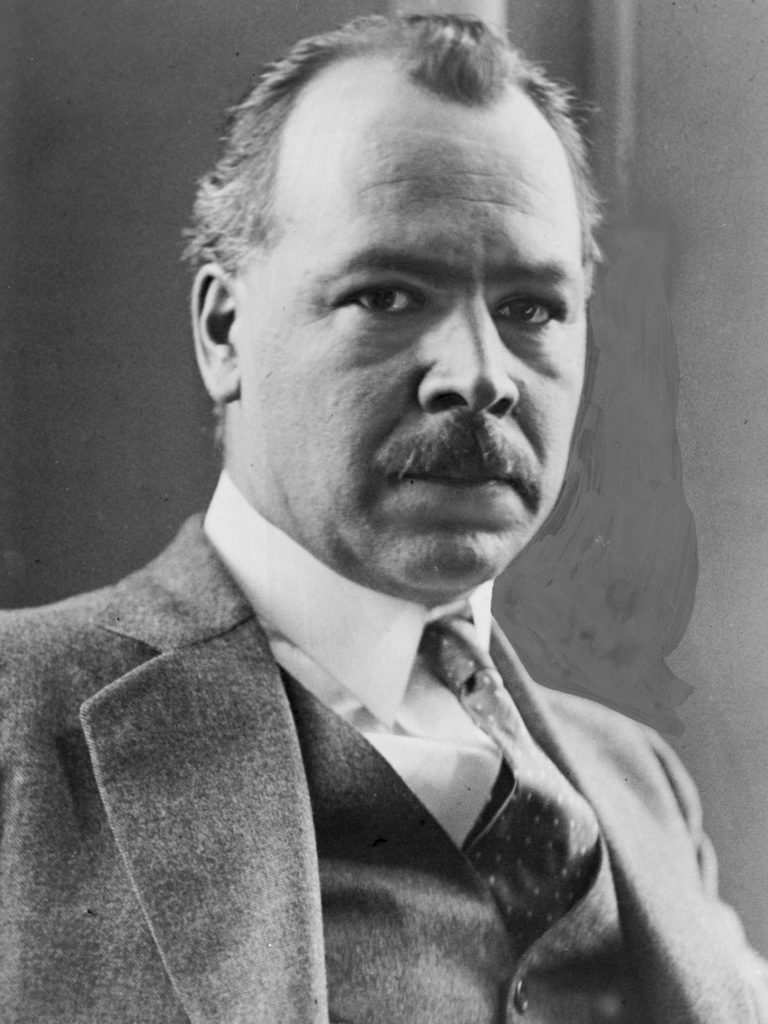

He was up to the task. He spoke several languages, had a photographic memory and was a tireless researcher. “Life is short,:” he wrote, “there is no time to lose.” His scientific abilities were recognized early, and he advanced rapidly through the ranks of Russian academia and government science. People liked him and gladly joined his mission. He traveled across the world on more than 100 expeditions, amassing a seed collection (what we now call a gene bank) of 250,000 specimens, the largest in the world at the time. He won awards (including the first ever Lenin Prize), led international botanical congresses, and wrote seminal works on plant distribution and diversity (today we would call that biogeography).

His work grew from the emerging understanding of genetics, based on the work of Gregor Mendel. Genes determined the traits of a plant, and those genes separated and recombined in ways that produced diversity in plant characteristics. That process could be guided by scientists to produce new hybrids with desirable traits. After disastrous crop failures in the new Soviet Union after World War I, the nation’s president, Vladimir Lenin, was looking for solutions—and he found Vavilov.

In 1922, when just 35, he was installed as head of the research institute that became the V. I. Lenin All-union Academy of Agriculture. He built the institute into a network of 400+ agricultural research stations across the country, employing more than 20,000 workers. As Russia Today states, he “was one of the most outstanding scientists of the twentieth century.”

When Lenin died in 1924, the country was taken over by Joseph Stalin. Gradually, a different concept of genetics took hold in the country. Led by Trofim Lysenko, a peasant farmer turned plant breeder, the new view was that organisms could inherit characteristics derived from their environment. Lysenko advanced a practice of chilling wheat seeds so they could be planted earlier in the spring, supposedly increasing yield. And seeds from those plants would then acquire the ability to live in colder conditions. This theory was wrong (acquired characteristics are not inherited), but that did not dissuade Stalin. Lysenko was from the proletariat, Vavilov was from the bourgeoisie; therefore Lysenko was correct.

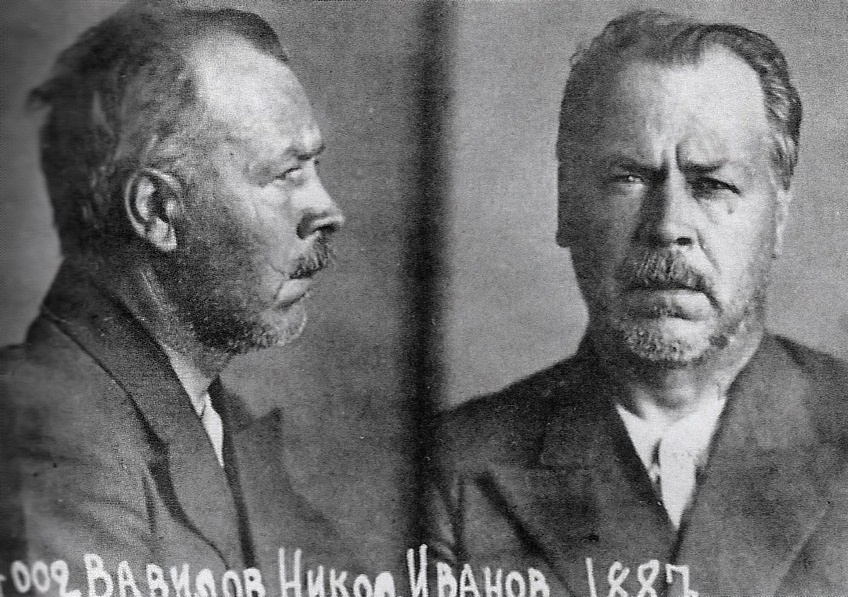

Vavilov refused to stand down. “We shall go to the pyre,” he said, we shall burn, but we shall not retreat from our convictions.” Convictions is what he got. In 1940, Soviet police arrested and imprisoned Vavilov for sabotaging Soviet agriculture, spying for England, and being a right-wing conspirator. He died in prison in 1943, when just 56 years old, and buried in a common grave without fanfare.

The passage of time, however, has restored Vavilov’s scientific and Russian reputations. His major works on the geographical locations of centers of plant diversity are acknowledged as the basis for new scientific fields in ecology and evolution. His pioneering gene bank led the establishment of many others across the world, one of the most important plant conservation strategies we have today. Scientific institutes across Russia now carry Vavilov’s name, as do streets in Moscow and St. Petersburg, glaciers and a crater on the moon.

So,the lesson is clear. In the longer term, truth will always prevail over lies, especially in science. The struggle may produce martyrs, like Nikolai Vavilov, but truth will always prevail.

References:

Janick, Jules 2015. Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov: Plant Geographer, Geneticist, Martyr of Science. HortScience 50(6):772-776.

Klevantseva, Tatyana. Prominent Russians: Nikolay Vavilov. RT Russiapedia. Available at: https://russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-russians/science-and-technology/nikolay-vavilov/. Accessed November 19, 2019.

N.I.Vavilov Institute of Plant Genetic Resources. Biography of Nikolai I. Vavilov. Available at: http://vir.nw.ru/test/vir.nw/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=88:00-biography-of-nikolai-i-vavilov&catid=28:02-nikolay-ivanovich-vavilov&Itemid=495&lang=en. Accessed November 19, 2019.