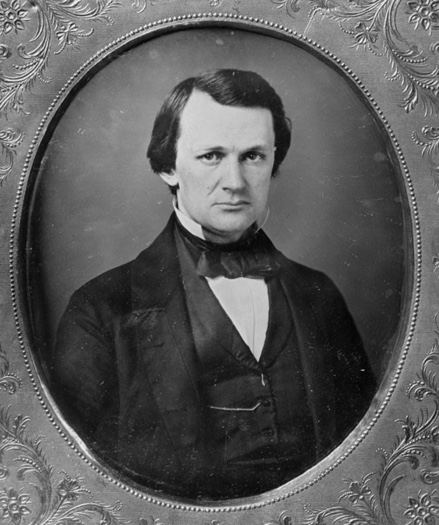

If you need an example of Type-A personality from the 19th Century, I’ve got your man. Spencer Fullerton Baird, born on February 3, 1823 (died 1887), held several jobs at the same time and in the process created our great national museums and our first foray into fisheries management. His name and picture should ber next to the dictionary definition of “overachiever.”

Baird was born in Reading, Pennsylvania. His father was a lawyer, but also a devoted naturalist. Father and son often tramped through the woods around Reading, studying the area’s natural history. Baird wasn’t a very good student, preferring to learn by observing nature in the field (a trait that he maintained his entire life). Obviously intelligent, he enrolled at Dickinson College at the age of thirteen and graduated with a B.S. four years later (right, when he was seventeen). He became friends with ornithologist John James Audubon and was a devotee of the work of Louis Agassiz at Harvard (learn more about Audubon here). After an unsuccessful try at medical school, he returned to Dickinson, receiving an M.S. in 1843. While in school, he corresponded with many of the leading naturalists of the era, including George Perkins Marsh, collected voraciously around the mid-Atlantic states, and published papers in biological journals. He became a professor of natural history and chemistry at Dickinson in 1845.

On the recommendation of George Perkins Marsh, in 1850, he was appointed to the Smithsonian Institution as Assistant Secretary of Natural History. Joseph Henry, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian, and Baird’s boss, was not interested in developing a large collection. Nevertheless, when Baird reported for his job, he brought with him his personal collection of biological specimens, numbering in the thousands and reportedly filling two railroad boxcars and weighing 8.5 tons. His job at the Smithsonian was generally routine and administrative, but he did the work willingly and with skill, earning the respect and tolerance of Secretary Henry.

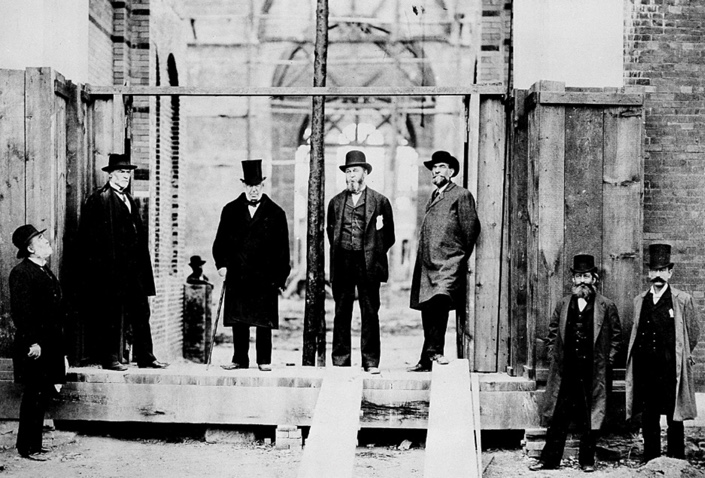

Tolerance was needed, because Baird never veered from his goal of building a large national collection (despite Henry’s indifference). His second job at the Smithsonian was to oversee the development of the National Museum, the portion of the institution that we now know as the National Museum of Natural History. In 1872, Secretary Henry formalized that work by appointing Baird as Director of the museum, with full control of its operations. He developed exchange programs with collectors and museums around the U.S. and world, gradually building the Smithsonian’s collections. His strategy, as he wrote to Marsh, was to accumulate such a large and unwieldy collection that Congress would be forced to appropriate money for both a building and the necessary staff to curate the specimens that filled it.

When Secretary Henry died in 1878, Baird was named his successor, becoming the second Secretary of the Smithsonian. With a free hand to develop the institution as he wished, he worked to build a new museum building, which opened in 1881 (now the Arts and Industries Building, next to the Castle), created a small zoo beside the Castle that evolved into the National Zoo, and added a program to study American Ethnology, primarily the cultures of Native Americans. He remained Secretary until his death in 1887.

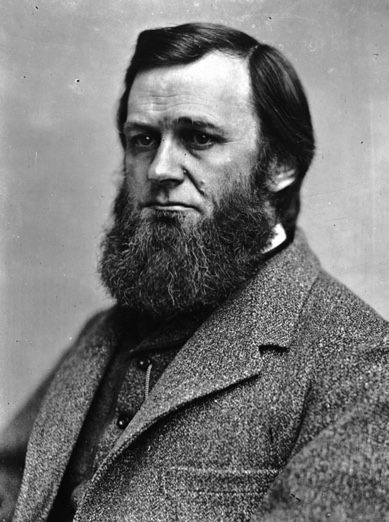

Baird’s other big job was one added to his responsibility in 1871. Concerns over the status of marine commercial fish species prompted the Congress to create the U.S. Fish Commission to study the situation and advocate for its improvement. They named Baird the first commissioner, a job that he was to undertake at the same time as pursuing his other responsibilities (with no additional pay) and that he also kept until his death.

Fish Commissioner was a job that Baird loved, perhaps more than his role as Secretary of the Smithsonian. He was always devoted to field work and natural history, although his leadership of the museum kept him from pursuing field studies as much as he wished. But as fish commissioner, designing and directing field studies was his primary task. To do so, he founded the Woods Hole Laboratory, which has become one of the world’s leading oceanographic and marine biological research institutions. He also authorized the construction of the first federal fish hatcheries and built two ocean-going research vessels (the Fish Hawk and Albatross) (learn more about the Albatross here). He spent as much time as possible at Woods Hole, especially during summer months when he invited the most distinguished marine scientists of his time to conduct research on the fish and aquatic biota of the Atlantic coast.

Baird was a distinguished leader and administrator of our nation’s greatest scientific bodies, a legacy enough for any person. But he also remained a prolific scientist himself, publishing more than 1200 papers and reports over his life. As the National Marine Fisheries Service writes in his biography, “Baird is credited with initiating the fields of marine ecology, fisheries biology or fisheries science, and laying the foundation of oceanography. He was also a pioneer in biogeography, the study of biological and geographic factors that influence the distribution of life on Earth. He believed research and education went hand in hand. From the start, he invited visitors to see what researchers were studying by displaying aquaria full of local species. He was convinced that in a democratic society, people are entitled to know about the activities of the institutions maintained with public funds.”

So, as you roam the great museum on Washington’s National Mall, reflect on the great men and women who made these things possible. Including one enormous overachiever named Spencer Fullerton Baird.

References:

Billings, John S. 1889. Memoir of Spencer Fullerton Baird, 1823-1887. National Academy of Sciences. Available at: http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/baird-spencer-f.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2023.

NOAA Fisheries. Spencer Fullerton Baird: Founder of the Woods Hole Laboratory and Fisheries Science. Available at: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/spencer-fullerton-baird-founder-woods-hole-laboratory-and-fisheries-science. Accessed February 24, 2023.

Smithsonian Institution Archives. Spence Fullerton Baird, 1823-1887. Available at: https://siarchives.si.edu/history/spencer-fullerton-baird. Accessed February 24, 2023.