What time was it at 34 minutes and 56 seconds past noon on July 8, 1990? If you take out all the punctuation, it was 1234567890! Playing around with numbers is great fun, and, since nothing else happened in conservation on any July 8 in history, let’s examine 8 important conservation and environment numbers today.

Number 1: 7.6 billion. The human population of the earth is somewhere in the upper 7-billions, the exact number depending on who you ask. This is the U.S. Census Bureau’s number; they also say the U.S., the world’s 3rd most populous country, has about 330 million. The world’s human population continues to grow at about 1.1% per year, but that is half the rate of growth during the 1970s, good news for all of us.

Number 2: 414 ppm. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the air at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, the world’s official number, was 414.58 ppm on March 18, 2020, but it goes up every day. And that carbon dioxide load gave us the hottest January on record in 2020, a full 2 degrees Fahrenheit above the temperature a century ago.

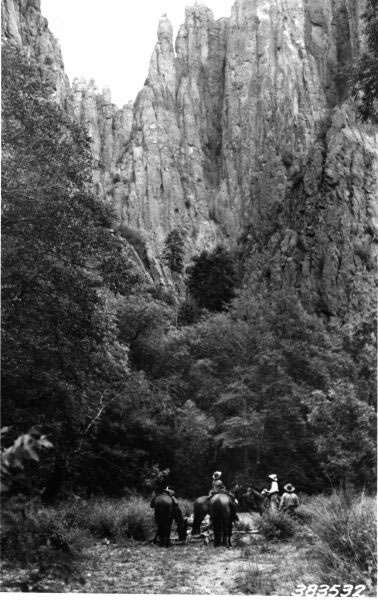

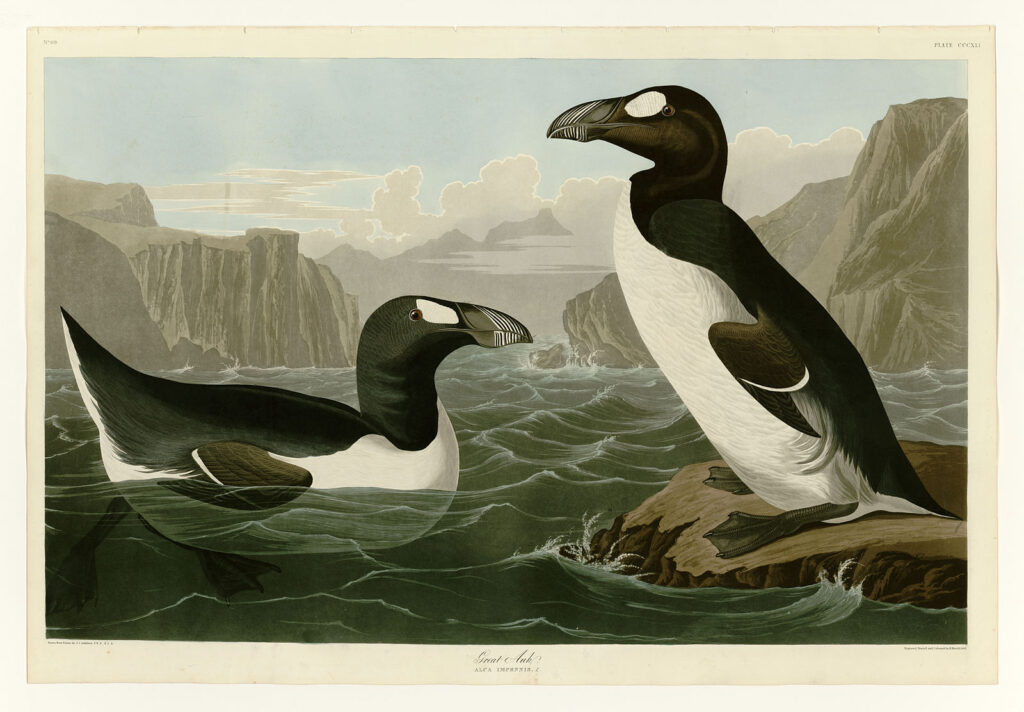

Number 3: 15.4%. That’s the amount of the world’s land area that is in protected status, as parks, preserves and other categories off limits to unregulated use. Combined, that’s about the size of South America. And then add about 3.4% of the earth’s marine area that is also protected. The total has more than doubled since 1990, and it continues to grow, especially for marine ecosystems.

Number 4: 1,864. That’s the best estimate of the number of giant pandas living in the wild, in China, during the last range-wide survey in 2014. The number is small, but it is a true success story. In the 1980s, the number was about 1,100 and dwindling. Now it is going up—17% in the last decade. This is such good news that IUCN has changed the status of the giant panda from “endangered” to “vulnerable.”

Number 5: 15%. Since 1970, the area of the Amazonian rainforest has declined by slightly more than 15%. Hidden in that number is both good and bad news. The good news is that the rate of deforestation has been dropping steadily—only about 1% of the loss has occurred in the last decade, as public opinion and Brazilian government policy both ruled against converting forests to pastures and cropland. And if you add re-forestation, the rate is about zero. The bad news is that Brazilian policy has reversed under the current president, and 2018 and 2019 saw deforestation rates bounce back up, to the level of a decade ago. Stay tuned.

Number 6: 65%. When Gallup Polls asked Americans whether they favored environmental protection over economic growth, or the reverse, 65% chose environmental protection. That number, in 2019, has risen, after a fall during the “great recession,” back to the levels in the 1990s. Even more promising is that 42% of Americans think the seriousness of global warming is generally underestimated, the highest percentage ever.

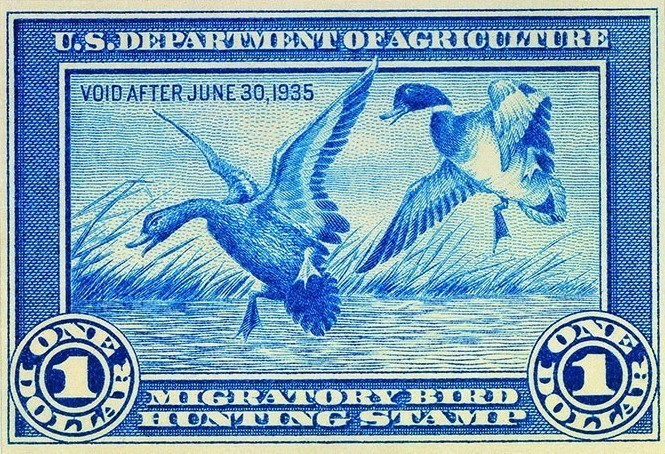

Number 7: 103.7 million. That’s the number of Americans, 16 years and older, who participated in wildlife-related recreation in 2016—41% of the population. That included 11.5 million hunters, 35.8 million anglers, and 86 million “wildlife watchers.” And 327.5 million people visited National Park Service properties in 2019—about one visit for every person in the U.S. (although some, of course, are overseas visitors). We do love our natural resources!

Number 8: 365 (or 366). Towards the end of his life, the famous nature photographer Ansel Adams said something like this: Every day, I try to do something for the environment, no matter how small. That’s a fine rule to follow, 365—or 366—days per year.