The Eagle is a famous pub not far off the high street in Cambridge, England. The pub has been in operation forever, it seems, but it owes part of its fame to the American Air Force servicemen who frequented The Eagle during World War II. The walls and ceiling are filled with graffiti left by the soldiers.

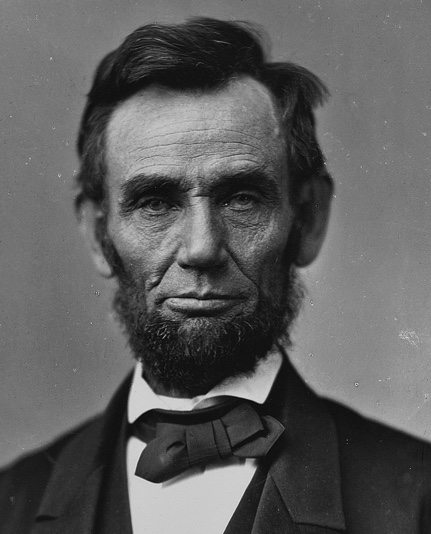

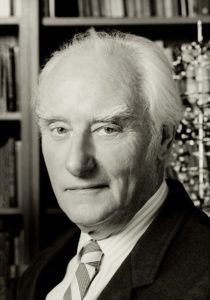

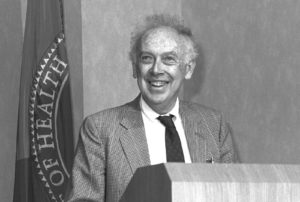

But it owes its more recent fame to the corner table where biologists James Watson and Francis Crick generally came for lunch or a drink and discuss their work on the mechanisms of genetics. And there, on February 28, 1953, they celebrated the conceptual breakthrough that is the basis for all we know about genetics today: the structure of DNA, the double helix.

Knowledge of the fundamentals of genetics was advancing rapidly at the time, including the understanding that deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was the building block for holding genetic information and transferring it to the next generation. But no one had figured out how it was done. Watson and Crick decided that discovering the three-dimensional structure of the gene was the key to unlocking the genetic mysteries. Just like the American flyers who relaxed at The Eagle had set their sights on German airplanes, Watson and Crick set their sights on the structure of DNA.

An essential step in the unmasking of DNA was the work of their colleague, Rosalind Franklin. Franklin was a physical chemist who had made her reputation studying the structures of other organic compounds. She was an expert at X-ray photography and her photographs of DNA gave Watson and Crick a fundamental idea about the structure of the compound. As both Watson and Crick subsequently and frequently reported, their discovery could not have occurred without her work (had she not died from ovarian cancer in her late thirties, today we might be talking about Watson, Crick and Franklin as three, not two, scientists credited with the discovery). Franklin and another collaborator of Watson and Crick’s, Maurice Wilkins, had used x-ray crystallography to suggest that DNA formed a corkscrew-shaped helix in three dimensions.

Another colleague, biochemist Erwin Chargaff, had deduced that four compounds (the bases adenine, guanine, cytosine and thymine) were always present in DNA and that adenine (A) and thymine (T) were always present in equal amounts, and the same for cytosine (C) and guanine (G). While working with cardboard models, Watson realized that two strands of the sugar-phosphate chains could be linked by hydrogen bonds of pairs of A on one strand and T on the other, or C on one strand and G on the other. When modeled this way, the structure was stable in a double helix. They had found the correct structure!

Not only was the structure consistent with all other evidence, but it provided the answer to how genetic information was transferred. The two strands split, and a new strand formed on the empty hydrogen bonds, A to T and C to G. With new strands built on the two separated parts of the double helix, an exact replica of the original compound was formed. And, when mistakes were made in the process, mutation occurred.

Watson and Crick went to lunch at The Eagle that day, triumphant over their discovery. Crick told the lunch crowd that they had “found the secret of life.” They published a one-page paper on their discovery in Nature on April 25, 1953, and a more complete version a month later (the same issue of the journal also included a paper by Franklin and her student that independently came to the same conclusion).

Well, of course, Watson, Crick, Franklin and Wilkins hadn’t discovered the secret of life, but certainly one of the secrets. Their discovery did provide the basis for understanding the mechanisms of genetics, and that itself has been enormously useful in understanding the processes that lead to diversity in nature. Because diversity is the essence of our use of nature, these scientists might just be among the most important conservationists of all time!

References:

Maddox, Brenda. 2003. The double helix and the “wronged heroine.” Nature 421:407-408. Available at: https://rdcu.be/clsdJ. Accessed May 27, 2021.

National Institutes of Health. The Francis Crick Papers; The Discovery of the Double Helix, 1951-1953. NIH U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available at: https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/SC/Views/Exhibit/narrative/doublehelix.html. Accessed February 23, 2018