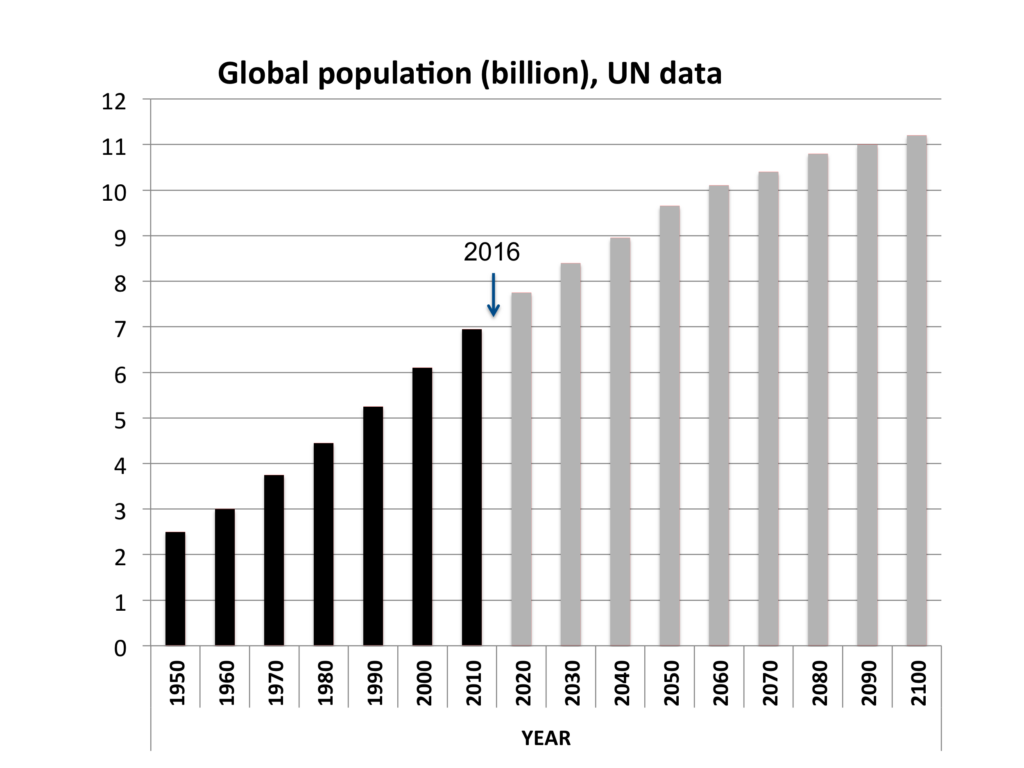

The United Nations has designated July 11 each year as World Population Day. This date was chosen in 1990 because it was the anniversary of the Day of Five Billion, when the world’s human population was estimated to have reached five billion individuals in 1989. Total world population in mid-2020 is around 7.6 billion people.

World Population Day is organized by the United Nations Population Fund, the primary global agency dedicated to reducing population growth by enhancing women’s health. Each year, the organization chooses a theme to highlight critical issues. In 2017, the theme was family planning, in recognition that “around the world, some 214 million women in developing countries who want to avoid pregnancy are not using safe and effective family planning methods, for reasons ranging from lack of access to information or services to lack of support from their partners or communities.”

Human population became a societal issue in the 1960s when the reality of rapid growth collided with fears about the ability of the earth to sustain large populations. Books like Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, published in 1969, predicted massive famine in the 1970s and the total collapse of India.

Fortunately, the dire predictions of the 1960s have not occurred. With increases in agricultural productivity and improved health in developing countries, population growth rates have fallen—perhaps a counter-intuitive outcome. But when quality of life improves, birth rates gradually decline. In the 1960s, the earth’s human population was expected to reach 15 billion individuals before stabilizing. Today, the stable population is predicted to be about 11 billion.

Despite this improvement, population continues to grow. The Day of Six Billion occurred on October 12, 1999, and the Day of Seven Billion on October 31, 2011. Each year, we add a net of about 80 million people to the earth—the equivalent of the country of Turkey. Birth rates are highest in Africa, and the continent’s total population is expected to double, from 1.2 billion to 2.4 billion, over the coming generation.

Consequently, continued attention to the reduction of population growth rate is needed. And the problem is a multi-faceted one, as UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has stated: “The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is the world’s blueprint for a better future for all on a healthy planet. On World Population Day, we recognize that this mission is closely interrelated with demographic trends including population growth, ageing, migration and urbanization.”

References:

Coleman, Jasmine. 2011. World’s “Seven Billionth Bay” is Born. The Guardian, 31 October 2011. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/31/seven-billionth-baby-born-philippines. Accessed July 11, 2017.

Sommerfeld, Julia. 1999. World Population Hits 6 Billion. NBC News. Available at: http://www.nbcnews.com/id/3072068/ns/us_news-only/t/world-population-hits-billion/#.WWUb64TytEY. Accessed July 11, 2017.

United Nations. World Population Day, July 11. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/events/populationday/. Accessed March 24, 2020.

United Nations Population Fund. 2017. World Population Day, 11 July 2017. Available at: http://www.unfpa.org/events/world-population-day.