How fitting it is that the man who led the creation of our great National Park Service should have been born on the 4th of July. Often called “America’s Best Idea,” the national parks of the United States have become a symbol of what democracy and freedom mean to a nation’s people. And we have Stephen Mather to thank for it.

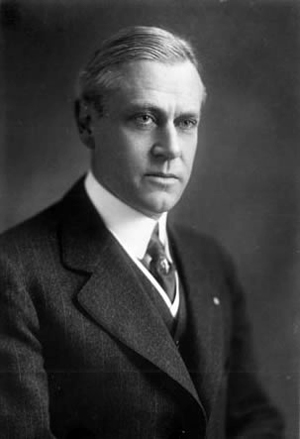

Stephen Tyng Mather was born on July 4, 1867 in San Francisco (died 1930) to a prominent family. He attended the University of California at Berkeley, graduating in 1887, and then became a reporter for the New York Sun. He later joined his father, working for a New York company that manufactured borax, a salt of the element boron and an important ingredient in detergents. Mather was charged with promoting his company’s rather routine product. To do so, he developed an advertising campaign around the name, “20 Mule Team Borax,” which became one of the most recognizable brands in America (ask your grandparents). Mather left that company and formed his own borax-manufacturing firm, becoming a wealthy millionaire as a result.

Mather was a model of American success. One admirer described him as “a figure larger than life—tall, blue eyed, ally of avant-garde poetry, a man of ‘colossal popularity’ in the business world, an ‘alloy of drive and amiability.’” But he also suffered from recurring bouts of depression, so severe that he sometimes required hospitalization. Mather had one reliable antidote for his depression—immersion into nature. He especially loved the country’s few western national parks, Yosemite and Sequoia in particular.

On a visit to those two parks in 1914, he was appalled by their condition. The parks were basically unmanaged, with no professional staff, shabby development and illegal use by miners, loggers and cattlemen. He wrote to the Secretary of Interior, a friend from college, complaining about what he saw. The Secretary wrote back, “If you don’t like the way the national parks are run, why don’t you come… and run them yourself.”

Mather did as asked, retiring from business and moving to Washington for a planned one-year stint as an unpaid leader of the national parks. He lasted for 25 years, becoming the first director of the National Park Service when formed in 1916. Through his genius, vision and hard work, he led the transformation of the parks into the treasure we know today. People liked him, listened to him, believed in him. In 1915, he conducted the “Mather Mountain Party” tour to several western parks; his guests included business leaders, elected politicians, scientists and the editor of National Geographic (learn more about National Geographic here) One later said, “If [Mather] was out to make a convert, the subject never knew what hit him.”

Mather fostered the legislation that formed the National Park Service in 1916 and then used his position as founding director to protect and enhance the parks. The 13 existing national parks and 18 national monuments were united under one agency, and each was assigned professional staff. Mather knew that the parks would succeed only if the public loved them, so he commissioned roads and comfortable lodging for the growing trend of automobile vacations. He developed policies that protected the scenic beauty of parks while also making their grandeur accessible to the public. He expanded the park idea into the eastern U.S., adding Shenandoah , Great Smoky Mountain (learn more about this park here), and Mammoth Cave National Parks. When money ran out, he paid from his own pocket, spending more than $250,000 over his term (at a time when the entire agency budget was $20,000 a year).

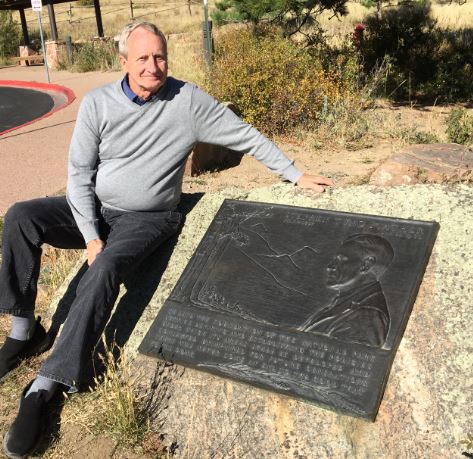

Although John Muir is remembered as father of the national parks (learn more about Muir here), Stephen Mather might be called their favorite uncle—adding discipline when needed but being great fun the rest of the time. Mather’s contributions are recorded in a small plaque displayed at most national parks today. It tells his story well: “He laid the foundation of the National Park Service, defining and establishing the policies under which its areas shall be developed and conserved unimpaired for future generations. There will never come an end to the good that he has done.”

References:

American Academy for Park & Recreation Administration. Stephen Tyng Mather. Available at: https://www.aapra.org/pugsley-bios/stephen-tyng-mather. Accessed March 13, 2020.

Public Broadcasting System. Stephen Mather (1867-1930). Available at: https://www.pbs.org/nationalparks/people/nps/mather/. Accessed March 13, 2020.

Schultz, Eric B. 2019. Preservation and Entrepreneurship: The Ongoing Impact of Stephen Tyng Mather. Gettysburg Foundation, September 16, 2019. Available at: https://www.gettysburgfoundation.org/gettysburg-revisited/blog-reimagining-gettysburg/preservation-and-entrepreneurship. Accessed March 13, 2020.

Swift, William. Stephen T. Mather. National Park Service: The First 75 Years. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/sontag/mather.htm. Accessed March 13, 2020.